ArtSeen

Anselm Kiefer: Exodus

On View

GagosianAnselm Kiefer: Exodus

November 12–December 23, 2022

New York, Los Angeles

The first impression you get walking into this show is weight. The weight of paint on canvas, a reminiscence of premodern painting, especially because the large size of these works means no one person could lift and hang them, so they defy domestic space. Then the weight of objects affixed to the canvases: shopping carts (apparently made in Kiefer’s studio rather than simply purchased), bicycles, clothing, the apparatus of the painter—brushes, pails, mixing bowls, palates. Then metaphysical weight: representations of ruins, evocations of Paul Celan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Exodus. Then, of course, the weight of German history, omnipresent in Kiefer, as well as his personal symbology, in this case the serpent that reappears in so many works here in all its complexity as a sign of renewal (shedding its old skin), energy, and danger. These are the works of a mature artist, perhaps in the most ominous sense: memories (an aid and a plague), emblems of despair (destroyed buildings), but despair mitigated by a will we find in Samuel Beckett’s “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

To begin at the beginning seems proper. The first piece in the show is Yezi’at Mizrayim (2020–21), a huge collage-painting (110 by 149 inches), composed of metal, fabric, word, terracotta, and paintbrush on canvas. The title refers, as does the entire show, to the Book of Exodus, the children of Israel leaving the slavery of Egypt behind, but not their memories of hardship. The piece puts us, like so many displaced persons in our time, on the road, but where does the road lead? To the Promised Land, to the desert, to death? Kiefer, in the lower register of the painting, piles in baggage carts, shopping carts, but also all the apparatus of the artist—brushes, palates, mixing bowls—so yes, we are among the millions condemned to migration, but we are also with Kiefer in his lifelong pursuit of his art. This thoroughly moving work is the ideal introduction to the rest of the show since it combines history, autobiography, and collective memory.

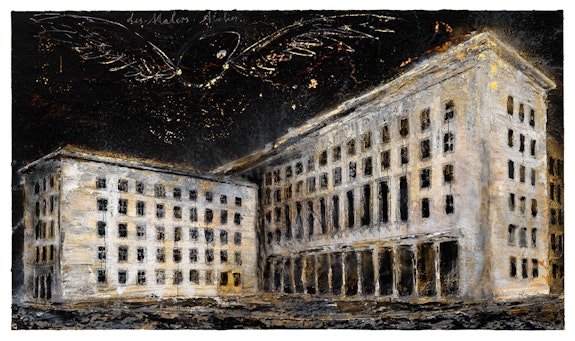

There are two works dedicated to the Romanian poet, both titled Für Paul Celan, both from 2021. These frightening paintings have less to do with any specific poem by Celan than they do with Celan as a Holocaust survivor and poet who lived only to produce poetry, clearly a model for Kiefer himself. The images show empty stone structures depicted at night. They might be prisons, they might simply be abandoned ruins, but they also constitute a portrait, especially if we think of them in the context of Jacques Derrida’s meditations on ruins in his 1990 Mémoires d’aveugle: L'autoportrait et autres ruines: “The ruin is the self-portrait, that face contemplated as a memory of itself.” So, the evocation of Celan is also a self-evocation, a haunting message of loss and salvation.

There are also two works here titled Exodus, one from 2021–22 and the other from 2022. These are monumental pieces, almost on a Veronese scale, the earlier measuring 185 by 330 inches and the latter 149 by 220 inches. They are both vast landscapes, though we cannot be sure we are looking toward escape from Egypt or looking back, as the Israelites did when they fabricated the Golden Calf of nostalgia. The only hint in the earlier work is a bicycle loaded with packages, a fragile piece of transportation for a precarious journey. The later piece, populated by human figures in the form of empty clothing, constitutes an icon for the migrant’s dilemma: standing in a no-place possessing nothing. The grand scale of these two works evokes the Romantic sublime, with its fears and dangers, accomplishing everything Kiefer seeks to accomplish: combining past and present.

Kiefer also dedicates two works to the German Romantic author E.T.A. Hoffmann, both from 2021. Hoffmann, especially in his novella The Golden Pot (1814/1819), specifically mentioned by Kiefer, stresses not the storm and stress of German Romanticism but the escape from bourgeois conformity and complacency through art. The two canvases are charged with Kiefer’s personal symbols: the ambiguous serpent, the empty dress, and real pails to link fantasy to reality. The “lightest” of the thirteen works assembled here, these constitute a flight from the vicissitudes of history and memory into the private world of creation.

No review can ever hope to elucidate Kiefer’s baroque complexity completely. Suffice it to say the master is at the top of his game.