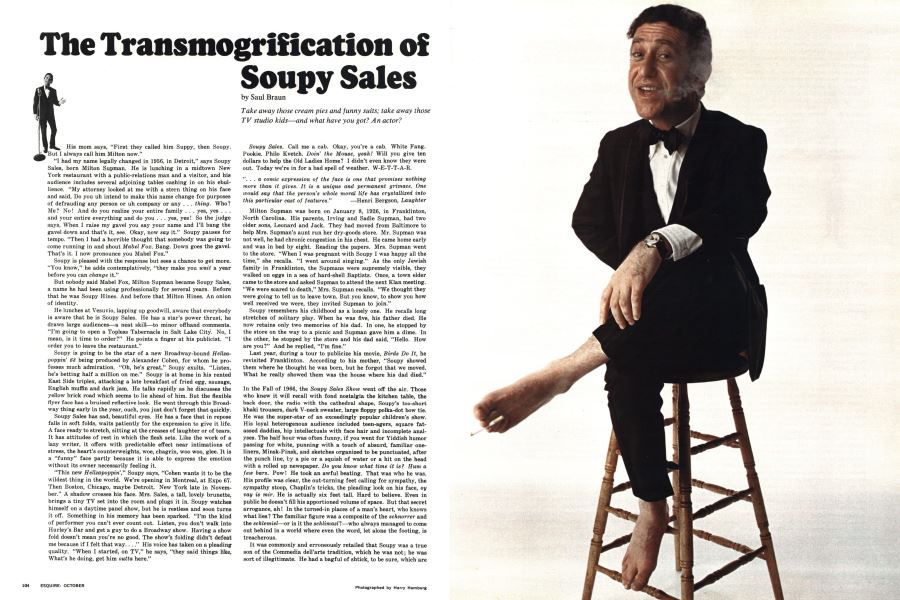

The Transmogrification of Soupy Sales

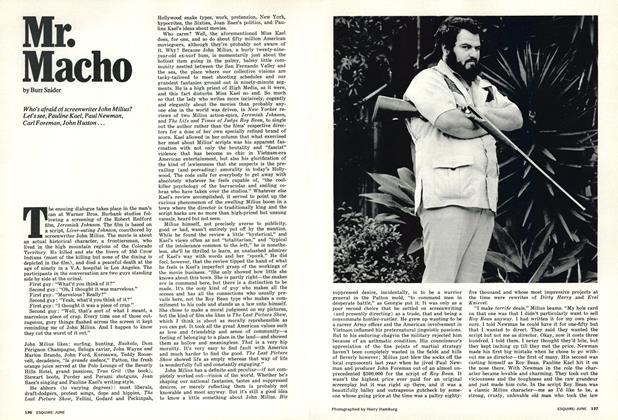

Take away those cream pies and funny suits; take away those TV studio kids—and what have you got? An actor?

October 1 1967 Saul Braun Harry HamburgTake away those cream pies and funny suits; take away those TV studio kids—and what have you got? An actor?

October 1 1967 Saul Braun Harry HamburgHis mom says, “First they called him Suppy, then Soupy. But I always call him Milton now.”

“I had my name legally changed in 1956, in Detroit,” says Soupy Sales, born Milton Supman. He is lunching in a midtown New York restaurant with a public-relations man and a visitor, and his audience includes several adjoining tables cashing in on his ebullience. “My attorney looked at me with a stern thing on his face and said, Do you uh intend to make this name change for purposes of defrauding any person or uh company or any . . . thing. Who? Me? No! And do you realize your entire family . . . yes, yes . . . and your entire everything and do you . . . yes, yes! So the judge says, When I raise my gavel you say your name and I’ll bang the gavel down and that’s it, see. Okay, now say it.” Soupy pauses for tempo. “Then I had a horrible thought that somebody was going to come running in and shout Mabel Fox. Bang. Down goes the gavel. That’s it. I now pronounce you Mabel Fox.”

Soupy is pleased with the response but sees a chance to get more. “You know,” he adds contemplatively, “they make you wait a year before you can change it.”

But nobody said Mabel Fox, Milton Supman became Soupy Sales, a name he had been using professionally for several years. Before that he was Soupy Hines. And before that Milton Hines. An onion of identity.

He lunches at Vesuvio, lapping up goodwill, aware that everybody is aware that he is Soupy Sales. He has a star’s power thrust, he draws large audiences—a neat skill—to minor offhand comments. “I’m going to open a Topless Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. No, I mean, is it time to order?” He points a finger at his publicist. “I order you to leave the restaurant.”

Soupy is going to be the star of a new Broadway-bound Hellzapoppin’ 68 being produced by Alexander Cohen, for whom he professes much admiration. “Oh, he’s great,” Soupy exults. “Listen, he’s betting half a million on me.” Soupy is at home in his rented East Side triplex, attacking a late breakfast of fried egg, sausage, English muffin and dark jam. He talks rapidly as he discusses the yellow brick road which seems to lie ahead of him. But the flexible flyer face has a bruised reflective look. He went through this Broadway thing early in the year, ouch, you just don’t forget that quickly.

Soupy Sales has sad, beautiful eyes. He has a face that in repose falls in soft folds, waits patiently for the expression to give it life. A face ready to stretch, sitting at the creases of laughter or of tears. It has attitudes of rest in which the flesh sets. Like the work of a lazy writer, it offers with predictable effect near intimations of stress, the heart’s counterweights, woe, chagrin, woo woo, glee. It is a “funny” face partly because it is able to express the emotion without its owner necessarily feeling it.

“This new Hellzapoppin’,” Soupy says, “Cohen wants it to be the wildest thing in the world. We’re opening in Montreal, at Expo 67. Then Boston, Chicago, maybe Detroit. New York late in November.” A shadow crosses his face. Mrs. Sales, a tall, lovely brunette, brings a tiny TV set into the room and plugs it in. Soupy watches himself on a daytime panel show, but he is restless and soon turns it off. Something in his memory has been sparked. “I’m the kind of performer you can’t ever count out. Listen, you don’t walk into Hurley’s Bar and get a guy to do a Broadway show. Having a show fold doesn’t mean you’re no good. The show’s folding didn’t defeat me because if I felt that way. . . .” His voice has taken on a pleading quality. “When I started, on TV,” he says, “they said things like, What’s he doing, get him outta here.”

Soupy Sales. Call me a cab. Okay, you’re a cab. White Fang. Pookie. Philo Kvetch. Doin’ the Mouse, yeah! Will you give ten dollars to help the Old Ladies Home? I didn’t even know they were out. Today we’re in for a bad spell of weather. W-E-T-T-A-R.

“. . . a comic expression of the face is one that promises nothing more than it gives. It is a unique and permanent grimace. One would say that the person’s whole moral life has crystallized into this particular cast of features.” —Henri Bergson, Laughter

Milton Supman was born on January 8, 1926, in Franklinton, North Carolina. His parents, Irving and Sadie Supman, had two older sons, Leonard and Jack. They had moved from Baltimore to help Mrs. Supman’s aunt run her dry-goods store. Mr. Supman was not well, he had chronic congestion in his chest. He came home early and was in bed by eight. Reading the papers. Mrs. Supman went to the store. “When I was pregnant with Soupy I was happy all the time,” she recalls. “I went around singing.” As the only Jewish family in Franklinton, the Supmans were supremely visible, they walked on eggs in a sea of hard-shell Baptists. Once, a town elder came to the store and asked Supman to attend the next Klan meeting. “We were scared to death,” Mrs. Supman recalls. “We thought they were going to tell us to leave town. But you know, to show you how well received we were, they invited Supman to join.”

Soupy remembers his childhood as a lonely one. He recalls long stretches of solitary play. When he was five, his father died. He now retains only two memories of his dad. In one, he stopped by the store on the way to a picnic and Supman gave him a dime. In the other, he stopped by the store and his dad said, “Hello. How are you?” And he replied, “I’m fine.”

Last year, during a tour to publicize his movie, Birds Do It, he revisited Franklinton. According to his mother, “Soupy showed them where he thought he was born, but he forgot that we moved. What he really showed them was the house where his dad died.”

In the Fall of 1966, the Soupy Sales Show went off the air. Those who knew it will recall with fond nostalgia the kitchen table, the back door, the radio with the cathedral shape, Soupy’s too-short khaki trousers, dark V-neck sweater, large floppy polka-dot bow tie. He was the super-star of an exceedingly popular children’s show. His loyal heterogenous audience included teen-agers, square fat-assed daddies, hip intellectuals with face hair and incomplete analyses. The half hour was often funny, if you went for Yiddish humor passing for white, punning with a touch of absurd, familiar one-liners, Minsk-Pinsk, and sketches organized to be punctuated, after the punch line, by a pie or a squish of water or a hit on the head with a rolled up newspaper. Do you know what time it is? Hum a few bars. Pow! He took an awful beating. That was who he was. His profile was clear, the out-turning feet calling for sympathy, the sympathy stoop, Chaplin’s tricks, the pleading look on his face, oy vay is mir. He is actually six feet tall. Hard to believe. Even in public he doesn’t fill his apportioned volume of space. But that secret arrogance, ah! In the turned-in places of a man’s heart, who knows what lies? The familiar figure was a composite of the schnorrer and the schlemiel—or is it the schlimazl—who always managed to come out behind in a world where even the word, let alone the footing, is treacherous.

It was commonly and erroneously retailed that Soupy was a true son of the Commedia dell’arte tradition, which he was not; he was sort of illegitimate. He had a bagful of shtick, to be sure, which are to Commedia lazzi as Dairy Queen is to Italian ices; they are somewhat the same thing. Pizza pie in the face? Never.

Soupy rarely bothered with character, he was always Soupy, gloriously Soupy. Like most American comedians who stand up barehanded to be funny, he called on his own resources, for the most part, and they were formidable. He braved the difficulties of live television; he wrote the scripts himself; he reported from the danger zone, “Just keep moving. A moving target is harder to hit.” When Soupy’s contract at WNEW-TV expired, he and his managers agreed he should spread his wings and fly. He had made a television special which has yet to appear, and his film, Birds Do It, received poor reviews. His personal manager, Stan Greeson, was undaunted, however. “I think he could be a major motion-picture force,” he said. “Or he could be an important Broadway star.”

One factor might prove ticklish: Soupy had no experience in the legitimate theatre. “The last time I was onstage,” Soupy said with a laugh, “was in the second grade. I was Peter Rabbit.” Nevertheless, Morton Gottlieb, producer of The Killing of Sister George, signed Soupy to star in Come Live With Me, a Broadway sort of comedy. Soupy was going to be an important star. He also, in all innocence, was entering the crucible and would transmogrify past the point of no return, to emerge in totally different substance, like a wafer caught in a ritual not of its own choosing.

Rehearsals take place at the Cort Theatre on Forty-eighth Street. The stage is bare save for the ugly, plain, stained benches that serve for couches, corners, doorways.

The back wall is washed white, hung with radiators and grills, and the actors’ words float up into the flies and the high ceiling beyond. Not an auspicious setting for comedy work.

Soupy is dressed in much the same outfit he wore on television, and is precisely what you’d expect the star of the Soupy Sales Show to be. He is full of optimism and constantly cuts up. Waiter, what’s that pig doing in my soup? A backstroke, sir. In the darkened theatre, the looming shapes shift and mumble and whisper. The co-author, Lee Minoff, hangs over the shoulder of the director like an old beady-eyed fox-fur collar that lifts its head up now and again to comment. The director is Jonathan Miller, the thirty-three-year-old British wunderkind who performed here in Beyond the Fringe. He talks rapidly, repeats phrases, chuckles appreciatively over Wittgenstein’s neat response to St. Augustine’s contention that he learned language from the pointing gesture. “Couldn’t have, you see. He needed language first to know what the pointing gesture itself meant.” Tall and loose-jointed, rickety ratchety, Miller is a great bird of prey or of sated repose, the owner of a watchful eye, the discreet mouth lines of one whose smile is often delicate and sardonic. His head is a Roman emperor’s, long-jawed, nose aquiline, all quirky-curly locks, lids heavy and sensitive as clitoral hoods.

“All right, people, let’s move along,” he says crisply. He is in grey flannels and blue blazer. He wears a lapel button, a little pink man on his hands and knees and the legend, “I am a creeping Socialist.” Miller works swiftly, with assurance, his goal a type of anthropometry. He is cool.

Soupy enjoys Miller’s control and his uncluttered paternalism. He rarely disputes and is never intractable. Because his is the largest role and because he is mostly innocent of traditional stage discipline, he requires more notes than the rest of the company. “Now then, Soup. You must be a little more imperiously abrupt, it should be a more elaborate satire. Oh, and you mustn’t discharge the energy, Soup, you must hold the tension like a coiled watch spring.” Soupy’s lines are delivered with little subtlety of inflection or color or tonality. He relies mostly on gusts of physical energy and the vigor of his voice, which is a marvelous instrument. It is thick and coarse, full of crunchy textures, and its patterns, massed inflections wheeling like gulls, allude to hard times in the cotton fields. There are thickenings familiar in the speech of the Southern Negro: lyrical, buoyant, pleading for notice. Somewhat more obscurely, but lurking there, sure enough, is the singsong querulousness of the Eastern European Jewish beggar. Soupy is humble, undemanding. “Once we were driving in a car with a chauffeur,” recalls Marc Richards, who left a thirteen-year job at the telephone company, complete with seniority, to join Soupy as a comedy writer, “and Soupy said, ‘Stop here, I want some coffee.’ He got out and he asked the chauffeur if he wanted cream and sugar in his. The guy was in shock. Soupy brought him coffee. Later, the guy told me that in all his years he never saw anything like it.”

Soupy chooses not to assume the prerogatives of power that go with stardom. He is like the king of a very small country traveling abroad, or a prince in exile. During rehearsals, he comes across lines he doesn’t like, and he says so, but he is hesitant, and won’t challenge Miller's authority. “That line is toilet,” he will say, but he won’t fight. He is devious and subtle, and often denies himself. His effort is to disarm by being himself disarmed. He carries no weapons. Instead, he dreams about the bad lines, wakes at midnight and prowls his house till three a.m. He won’t admit to feeling tension. Even when the author gives him a reading, during notes, Soupy listens politely.

“Ordeur,” Lee Minoff says. “Like a voyeur, only with ears.” There is a long hushed moment as all consider the line’s comic potential. Above Soupy’s head, in a balloon, large elegant type forms the letters t-o-i-l-e-t. But he says nothing. He is enraged, feeling nothing, impassive.

“I don’t mind criticism,” he says back in his dressing room, changing his clothes rapidly and one would say angrily. “I never mind criticism if it’s constructive. That’s . . . I know timing. I’ve written more scripts than he ever will!”

He saunters out, nattily dressed, and spots Hanne Bork, the beautiful Danish girl who is playing the ingenue, and whose accent is pronounced. “Hanne, you’re doing fine,” Soupy tells her. “Everytime you say something I look down at your chest for the subtitles.” Not bad for the illegitimate son of a fine old comedy tradition. Therapeutic shtick, good for what ails you.

Carlo Goldoni, the Italian playwright who was heir to the Commedia dell’arte, did away with the Commedia masks in order to enhance the possibility of characterization. “. . . the soul under a mask,” said Goldoni in his Memoirs, “is like fire under ashes.”

Soupy’s dad died of an asthmatic condition in 1932, at the age of forty-four. Three years later the family moved to Huntington, West Virginia, a city of about 75,000, and Sadie Supman opened up the store again. She had remarried, in 1934. The stepfather, Felix Goldstein, was a traveling salesman for a pants manufacturer. His territory was West Virginia, Ohio and Kentucky. He was out all week, home on weekends.

“Felix and Soupy were as close as any father and son,” recalls oldest brother Leonard. “They enjoyed each other’s company. Felix would say, ‘Tell me jokes, entertain me,’ and Soupy would.”

“Felix was from Vienna,” says Soupy’s mom. “He and Soupy were buddies. Felix wanted him to go into a profession like his older brothers, but Soupy said, ‘Pop, I’m interested in radio. That’s what I want.’ In 1950, Felix was killed in an automobile accident. Soupy took it awful hard. They were such buddies. In just ten or twelve days, Soupy lost about twelve pounds.”

“My stepfather died in 1950,” Soupy recalls, “and, well, it really bothered me that he didn’t mention me in his will. I guess I was closer to him than he was to me. I love people. I really do. I’m a very sentimental guy. Well, I guess he was thoughtless. He didn’t even leave me his typewriter. I mean, well, I didn’t really care, it was just. . . .”

Soupy is offered a costume hat that doesn’t appeal to him. For reasons that are hard to fathom, he takes a stand. He will not be pushed around on this. He appears from the wings of the Shubert in New Haven shaking the hat, his face flooded with color. “This hat. Look at it.” All activity ceases. Down in the house, at the lighting designer’s command post, Jonathan Miller looks up. “What’s wrong with the hat, Soup?” “Well, look at it. I . . . won’t . . . wear . . . this . . . hat. I wouldn’t wear this hat to a cat screw!” Miller clears his throat. “Well . . . Soup. I’ve seen hats like that at many a cat screw.”

Soupy wins on the hat thing but it doesn’t improve his mood. He has settled into a more or less permanently morose state which he refuses to acknowledge. His rehearsal shtick turns even more self-deprecatory than usual, he hurls himself about the stage recklessly, and commences running into doors to get a laugh from the company.

Wearing elbow and kneepads doesn’t prevent him from tearing a ligament in his back. “Oh, my God,” says the producer, “get a doctor.” Jonathan rises up grandly and says, “I am a doctor.” What a moment! He really is a doctor. He rushes onstage and begins tapping Soupy’s spine desultorily. Eventually a local doctor shows up and Jonathan announces happily that the local man has prescribed what Dr. Miller would have.

“Actually,” he confides, “Soupy’s not fit. He’s not in shape for this sort of thing.” Within a week or so, the play’s weaknesses begin to appear insurmountable. “I constantly have to remind myself that I’m a doctor,” Jonathan says. He shrugs his shoulders helplessly. “Well, I’ve done all I can do, I think.” The following week while they are in Philadelphia, it is announced that Jonathan Miller is leaving the show. “What really bothers me,” Soupy later confesses, “is that he didn’t even bother to say good-bye.”

Snapshots: A Career Album

“We had a neighbor, Mrs. Shearin,” Soupy’s mom recalls. “Her son Willie was eating cookies and Soupy said, ‘I like cookies; my mother won’t let me ask for them, but I like cookies.’ That really won her over.”

“In high school I performed at assemblies,” Soupy says. “I used to imitate bands.”

“After I moved to Lancaster, Ohio,” says older brother Jack, an attorney, “I got a call from Soupy. He said, ‘Guess what, I got a date playing in a nightclub up there.’ I said, ‘We don’t have any nightclub up here.’ He said, ‘Now you do,’ and he named it. Well that was just a hillbilly place where everybody was drunk and where they charged a twenty-five cents cover on Saturday night. In his act there Soupy did a takeoff on Sam Spade and he strummed a banjo.”

“I was attracted to him because he was in show business,” says Barbara Sales. “When he had his disc-jockey show in Huntington he was the biggest thing in town. He was a real dude. He wore suede shoes and a chesterfield with a hankie in his pocket. You know.”

“Cleveland was his difficult years,” says Fred Shorsher, a New Jersey stockbroker. “He moved into an apartment right across the hall from us. Their furniture hadn’t arrived and we had to lend them a mattress and a card table and they set up housekeeping. He had a deejay show on WJW that drove parents wild, with sound effects, noises, lots of brassy music. Then he lost some of the sponsors.”

“I went home to Huntington with the baby,” Barbara recalls.

“My first year in Detroit I made $13,000,” Soupy says. “Then $26,000. Then $70,000 and finally over $100,000. I was the highest-paid local TV performer in the country. John Pival, the general manager, was a sort of father figure to me. In 1960, I told him I was leaving Detroit and he understood. But we’d go out drinking and the animosity would show, he’d begin insulting me. I guess he thought I was deserting him. It felt like he was losing a son, I guess.

“After the Jell-O Show ended in Los Angeles,” Soupy says, “I was a member of the four or five things club. You know, a guy asks you what you’re doing and you say, ‘Oh, four or five things.’ In the eight months before I went to New York, I only worked two weeks.”

“I was told that Soupy was difficult to deal with,” says Art Seidel, formerly the producer of the Soupy Sales Show and now vice-president of Emenee, a toy company. “They asked me to produce his show because I had a reputation for being a strong producer who knew the business. But Soupy was the easiest fellow to get along with I ever knew.”

“Soupy didn’t like WNEW,” says Kathy Kirkland, president of the Soupy Sales Fan Club. “There’s a man there named ‘Fats’ Bailey, kind of short and fat and I think he has glasses. When they taped the last show that was on the air on September 6, 1966, there were about eight hundred kids there and ‘Fats’ came out and they all booed and hissed. ‘Fats’ gave Soupy a bad time.”

“Channel Five was like the Twilight Zone,” says Marc Richards. “Now Soupy’s beautiful, a beautiful human being, but finally even he had enough. Once he showed up and the set wasn’t ready, it wasn’t lit, nothing. So he walked off. First he called Stan Greeson, his manager, to make sure, and Greeson agreed, he said Soupy had every right.”

“Not once did the management come out and say, ‘You’re doing a good job,’ not one nice word,” Soupy recalls.

Joshua Shelley is red-faced, bony, wiry, a man of high energy who has a springy Groucho Marx walk. Soupy was elated to learn that Shelley had replaced Jonathan Miller. He is all the things Miller was not; Shelley is kind enough, tough enough, old enough. He is j-u-u-st right.

“I’ll get you better lines, babe, honey,” Shelley says. “Ï give you my word as a Jewish gentleman that I’ll be in with that boy all night getting you lines. I’m working to extend the reality of the play. This is a musical with the first ballad missing, you know, ‘I’m a lucky boy, You are lucky, too.’ Nobody believes this thing so we have to start with Once Upon A Time.”

Soupy is enamored of his new director, having a wonderful time. His mood has snapped. He brings back, in all its flowering, his epic shtick cycle. Ashtray balances on his fingers. “You think that’s too much for an engagement ring?” Ashtray to his face. “You think that’s too much for a monocle?” “Go to work, Soupy,” Shelley urges. “I’m going to drive to Bermuda,” Soupy goes on. “But there’s no road to Bermuda.” “That’s all right, I’ll just keep the windshield wiper going.” “SOUPY! STOP IT! GO TO WORK!” Soupy is hard put to stop all at once. “Paul Hodges, in Cincinnati, a great old guy, he used to say, ‘When in doubt, drop your pants.’” Shelley laughs and together they dance across the bottom of the stage. Shelley turns serious, however. “Hey Swan Lake, hey Soupy. You get no allowance this week and no TV on Monday.” Soupy laughs. “You think I’m kidding? You see that seat? Walter Kerr. Walter Kerr.” Soupy sniffs. “Oh, what’s the use,” Shelley groans. “What’s the point of being King of the Jews if nobody listens to you! Souplah, listen, do you know when we open?” “No,” says Soupy, “but if you hum a few bars I’ll fake it.” “MILTON! IF YOU DON’T BEHAVE. . . .”

Later, Soupy walks into Danny’s Hide-A-Way, a favorite hangout in New York, and there is round-faced Totie Fields, a comedienne who has appeared as a guest star on Soupy’s old show. She rears back and extends her arms to engulf him and heaves an adoring, full-breasted sigh. “Oh, there he is. My Broadway star.”

On opening night, Soupy’s dresser, twenty-four-year-old Mark Klein, is having a difficult time getting from place to place. Soupy’s dressing room is mobbed. Klein, who has, in his time, dressed George Grizzard, Pat Hingle and Ray Milland, is in a state. “This is the worst I’ve ever had it ever with people backstage,” he complains. It is, in fact, a typical star’s opening night, save for the one implausible note struck by Soupy’s mom, who stands at the door to the dressing room and shakes hands with all who enter, announcing proudly, “I want to shake your hand, I’m Soupy’s mom.” Somewhere in the crush are Kathy and Diane Kirkland, twins and co-presidents of the Soupy Sales Fan Club. They are from California, very pretty and chic in new evening gowns. They have spent small fortunes to come East, have already seen the show six times in preview performances, and for their devotion have been invited to the opening-night party.

Two long black Cadillacs pull up in front of the theatre. Kathy and Diane hop into one of them, leaving behind about thirty grim-faced members of the fan club. “Boy, will they be mad,” one of the girls exults. The uniformed chauffeur, Barry Keit, is also, by coincidence, a fan of Soupy’s. “For me, the show that Frank was on was it. When he hit the King in the face with a pie, that cemented him with me.”

Soupy enters Danny’s Hide-A-Way to a brisk, spontaneous round of applause which follows him upstairs to the private room on the second floor where sixty or so guests have gathered to have fun and celebrate. At one table sits Soupy’s family. “Yes,” Leonard is saying, “what he has attained in his area I’ve matched in mine. I’m on the State Board of Examiners for Optometrists and a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. I guess you could say I was a father figure for him, He always calls to fill me in, just like a boy checking in with his mother. We always think of him as the kid.”

“We frankly felt the kid would starve in show business,’’ adds brother Jack. “Money doesn’t mean a thing to him. He’s only interested in prestige and personal success.”

“Show business people are egotistical,” Leonard says.

Everybody has a great deal of fun, laughing and drinking and going up to the buffet for thirds on the filet mignon. Earl Wilson wanders in for a good quote or two, and after the television reviews, which are not too good. Rona Jaffe wanders around commenting on television critics. Soupy’s face has begun to wobble. In anticipation of what is to come, Soupy and Barbara and Stan Greeson move upstairs to the private room on the third floor. Bernie Ilson, the publicist, shows up with wet copies of The Times, and it is as everybody feared. Earlier in the week, Soupy had dreamed that Walter Kerr had thick wrists.

The review proves to be as painful as Soupy had dared dream it would be.

He picks up The Times and slowly rereads the entire review, which was quite long, in a dazed, deliberate monotone. Barbara is quite close to him, stroking his head. His features sag, and he takes on a distant, longing look. He seems simultaneously trapped and released.

Downstairs, his brothers are feeling left out. “Where I come from we think it’s rude for a host to be absent from his own party,” Leonard says. Then somebody discovers that Soupy is upstairs and they all troop up, followed by Rona Jaffe. At the top of the stairs it becomes apparent that things are not well. Slowly, reluctantly, as if bidden to the funeral of a distantly loved and not altogether admirable relation, they walk over to Soupy’s table. His mother sits down, his brothers stand. All assume strained postures of solemn discomfiture. They look away embarrassedly. It is a family grouping of such pertinency, their inability to face Soupy’s emotion so evident, that it seems to a suggestible bystander the reaffirmation of what can only have been an ancient, time-honored family pact; perhaps even the bargain that brought them all to that spot.

Barbara strokes him, reminding him persuasively of his past fortitude, giving him compassion and comfort.

Soupy begins to weep.

He appeared to heal rapidly. He made appearances on the late night variety shows, notably the Johnny Carson Show, telling long involved jokes about his publicity-happy dog Beauty, or other large dogs, which he does well. But he seems ill-at-ease, rushed, as though he were breaking in a new act, and he laughs in an odd way. “Listen,” he had told Jonathan Miller many weeks earlier, “the guy who’s doing the bit is the first to know it isn’t working.”

Late-night shows, early-morning and afternoon shows, guest spots on other people’s shows. Soupy does not enjoy it, he feels in limbo. He knows he can’t turn around and go back, yet he seems not to have identified his new audience. “You know what it is,” Johnny Carson tells him. “You tell your stories as if you expected them to bomb.” Soupy doesn’t like to hear this. Not even from Johnny Carson. He doesn’t like it a bit.

According to his manager, he has been offered (and has turned down) summer stock at seven, eight thousand a week. He has also turned down the job of emceeing the new late-night Las Vegas Show at a comparable price. “Las Vegas is no place to take a family,” he gives as the reason.

He flies to the Coast. He flies L.A. to N.Y. He gives a party and shows a movie, but the projector doesn’t work. His noontime vivacity is not his best work. Late at night he waves the white flag. He whistles bravely. “People like me. It sounds braggadocious I know, but they do. They come up to me on the street and embrace me.” Alexander Cohen offers him Hellzapoppin’ and suddenly things are looking up. He is ready to go another round. Is he nervous? “No, not at all. I really was never nervous in the play. Listen, it’s like that old joke. I’m going to do it until I do it right. I’m going to do it until I get that hit.” He flicks on a large color television set to catch the end of a noontime panel show in which he took part, but before the picture appears, he flicks it off again. “What the hell, we don’t want to sit here watching me on television. I know exactly what’s going to happen with Hellzapoppin’. People will love this show, as before. Critics will say they didn’t do it as good as Olsen and Johnson. Critics will always compare to what happened before. Can it be brought off? That’s the challenge. Well, I’m an optimist.”

“You shouldn’t make jokes,” Alice said, “if it makes you so unhappy.”—Lewis Carroll

Soupy is at a private party. He balances an ashtray across his fingers. “You think that’s too much for an engagement ring?” He wheels around a large oak coffee table, turning it. “All right, I’m going to flood the gates and drown us all.” To the twin five-year-old sons of the host, who have been promised a dialogue with Soupy Sales, he says, “Which one of you is Leopold and which one is Loeb?” It is a witty effort, notwithstanding the fact that they don’t get it. The boys are fascinated with him. One asks him to do the Mouse, and he does, graciously, though he isn’t overjoyed to do it. The boys follow him around for some minutes, peering wide-eyed at him from behind chairs and couches and end tables until finally it dawns on them that he isn’t as taken with them as they are with him. Soupy has already turned with evident relief toward the adults, has launched onto a long, complicated story about his publicity-hungry dog Beauty. The twins, with the ineluctable precision of young accountants, close the books on him. They immediately lose interest in him and go away of their own accord. As far as they are concerned, Soupy Sales is no longer a presence out of the pantheon suddenly and marvelously deposited in their living room, but just another noisy adult at a big person’s noisy gathering. They walk slowly down a forty-foot-long hall, getting smaller and smaller, until finally they disappear into their bedroom.

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Articles

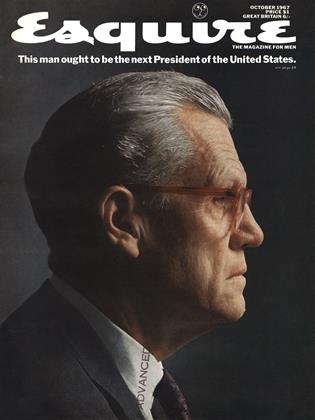

ArticlesIs It Too Late for a Man of Honesty, High Purpose and Intelligence to Be Elected President of the United States in 1968?

October 1967 By Steven V. Roberts -

Articles

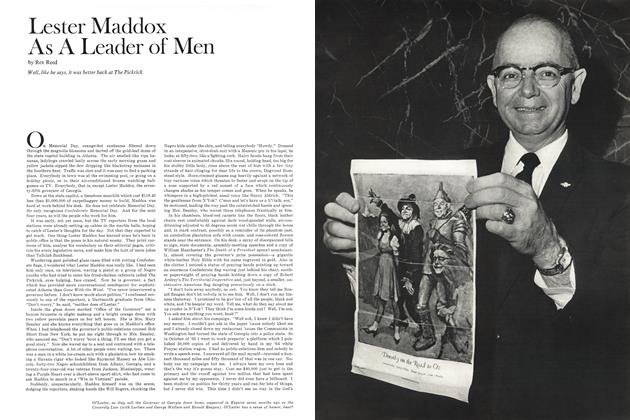

ArticlesLester Maddox as a Leader of Men

October 1967 By Rex Reed -

Fiction

FictionThe Wheel of Love

October 1967 By Joyce Carol Oates -

Articles

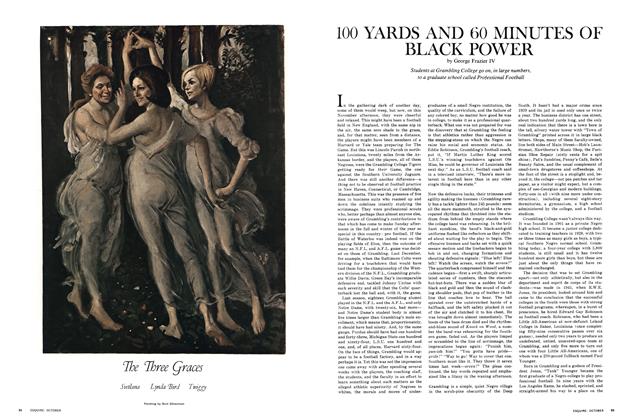

Articles100 Yards and 60 Minutes of Black Power

October 1967 By George Frazier IV -

Articles

Articles47 Places in America to Buy Land and Make Money

October 1967 By William H. Robbins -

Fiction

FictionKessler, the Inside Man

October 1967 By George Fox

Unlock every article Esquire has ever published. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to every timeless profile, interview, short story, feature, advertisement, and much more!

More From This Issue

Saul Braun

-

ARTICLES

ARTICLESI Mean, My God, If You Can’t Produce a Great American Novel for Two Hundred Thou, Pre-Sold to the Flicks, What the Hell Hope Is There for American Literature?

FEBRUARY 1967 By Saul Braun -

THE MEDIA GENERATION

THE MEDIA GENERATIONLife-Styles: The Micro-bopper

MARCH 1968 By Saul Braun -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESUntil Joey Bishop, Merv Griffin and Johnny Carson Do Us Part

AUGUST 1968 By Saul Braun