For those of us old enough to remember the tumultuous year 1973, when the Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion as a constitutional right, today’s upheavals have unmistakable and instructive similarities.

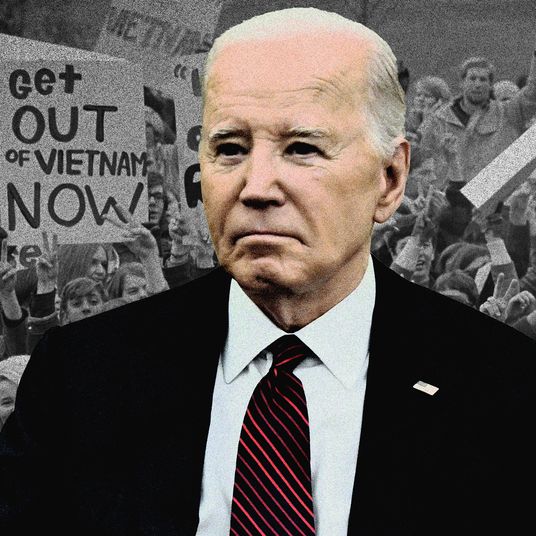

Then, as now, the U.S. was formally wrapping up — and recovering from — a costly and unpopular war. U.S. troops ended the 20-year engagement in Afghanistan a few months ago in an echo of how in 1973, less than a week after the Roe ruling, the signing of the Paris Peace Accords officially ended the Vietnam War, with the last American military unit leaving the country two months later.

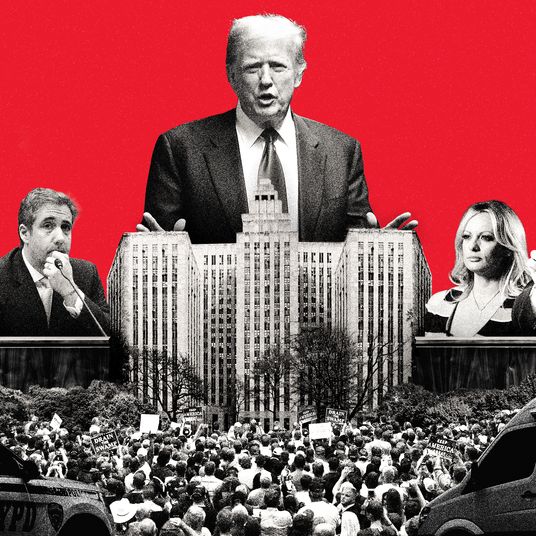

Then, as now, wrongdoing in the White House threatened the very core of democracy. The upcoming congressional hearings on the January 6 insurrection will likely make for riveting television, much the way the investigation of criminal activity by top aides to President Richard Nixon — notably the botched break-in of Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel — exploded into public view in 1973 when televised hearings began.

Today’s skyrocketing price of gasoline triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is reminiscent of the Arab oil embargo launched in 1973 by Middle Eastern petrostates, led by Saudi Arabia, as a form of retaliation following that year’s disastrous Yom Kippur War, when a coalition of Arab nations attacked Israel and was defeated with help from the United States.

The oil boycott triggered high inflation and an economic recession in the U.S. Sound familiar?

If we old-timers act as if today’s crises don’t signal the imminent arrival of Armageddon, it’s partly because we’ve lived through comparably messy and frightening political moments — but mostly because we can see the enormous differences between then and now.

In 1973, there were only 16 women serving in the 93rd Congress. It was a powerhouse group that included Shirley Chisholm, Bella Abzug, Barbara Jordan, Elizabeth Holtzman, and Ella Grasso. But there were no women senators at all. (The House, after centuries, named its first female page that same year.)

Today, the 117th Congress has a record-high 120 women serving in the House (including Speaker Nancy Pelosi) and 24 women in the Senate, not counting Vice-President Kamala Harris, who ceremonially presides over the body and can cast tie-breaking votes.

The early draft of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization opinion shows Justice Alito hell-bent on settling scores with the justices who decided Roe (all of whom are deceased). Alito makes no attempt to shield his contempt for the reasoning behind Roe, resting his argument on the fact that the Constitution makes no reference to abortion and suggesting that no such right exists.

“Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito is surprised that there is so little written about abortion in a four-thousand-word document crafted by fifty-five men in 1787,” Harvard professor Jill Lepore notes in the New Yorker. She goes on:

“There is nothing in that document about women at all. Most consequentially, there is nothing in that document — or in the circumstances under which it was written — that suggests its authors imagined women as part of the political community embraced by the phrase ‘We the People.’ There were no women among the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. There were no women among the hundreds of people who participated in ratifying conventions in the states. There were no women judges. There were no women legislators. At the time, women could neither hold office nor run for office, and, except in New Jersey, and then only fleetingly, women could not vote. Legally, most women did not exist as persons.”

That is the big difference today. In the year Roe passed, second-wave feminism was in full swing and gathering political and cultural momentum. Helen Reddy’s anthemic “I Am Woman” won a Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance in 1973. In pro tennis, a much-ballyhooed “Battle of the Sexes” at the Houston Astrodome pitted a young Billie Jean King against an aging ex-champion, Bobby Riggs, a self-described “chauvinist” who lost in straight sets before an audience of 90 million viewers.

Half a century later, women have steadily grown in social and political power, now outnumbering men in law schools year after year and recently becoming a majority of new medical doctors. We continue to see high-profile breakthroughs, like Boston electing its first woman mayor and New York’s first-ever City Council with a female majority.

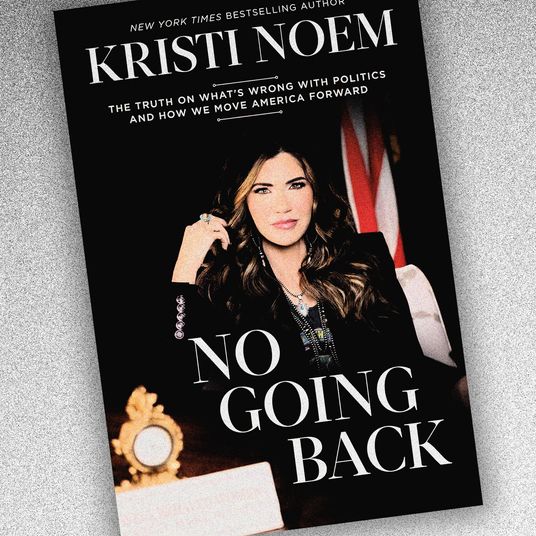

Whether Alito and other anti-abortion activists like it or not, the coming fight over abortion will include a sizable body of women leaders among — and in many cases, running — county boards, statehouses, Congress, and the high court itself. They are not a monolith; the fifth and deciding vote for Alito’s attack on Roe will likely come from Justice Amy Coney Barrett. But a great many are inclined to agree with Lepore’s thought that “women are indeed missing from the Constitution. That’s a problem to remedy, not a precedent to honor.” Coast-to-coast mobilizations have begun.

A notable lack of gloating or elation from right-wing officials suggests that Republicans know that the court’s conservative majority has kicked a hornet’s nest. The midterm elections in six months will tell us whether Democrats will have the energy and discipline to sting back.