Anselm Kiefer’s recent exhibition, Golden Age, at Hong Kong’s Villepin Gallery, brings together a series of paintings that explore the myth and reality of the utopian idea.

The past plays an integral role in German artist Anselm Kiefer’s work. Born in 1945 in Donaueschinge, Germany, not long before the end of the second world war, Kiefer grew up in a place and time when those who had survived it would rather not discuss the war. “The quasi natural reflex, engendered by feelings of shame and a wish to defy the victors, was to keep quiet and look the other way,” writes W.G. Sebald, a writer who like Kiefer also grew up in post war Germany and whose work is preoccupied with the destruction and rubble of the war. In defiance of what he experienced around him Kiefer set about creating work that confronted history, with its ugliness, shame, horror and guilt, and creating works that are a testament to the past.

Through a long process of layering materials, paint, and motifs Kiefer reworks and circles back to the same themes in his oeuvre— destruction, recreation, and the cycle of life and history. The ruins and rubble of the war served as his playground and would become a leitmotif in his work. In a way, Kiefer’s paintings are an act of remembrance, concerned with the preservation—and decay—of history and memory.

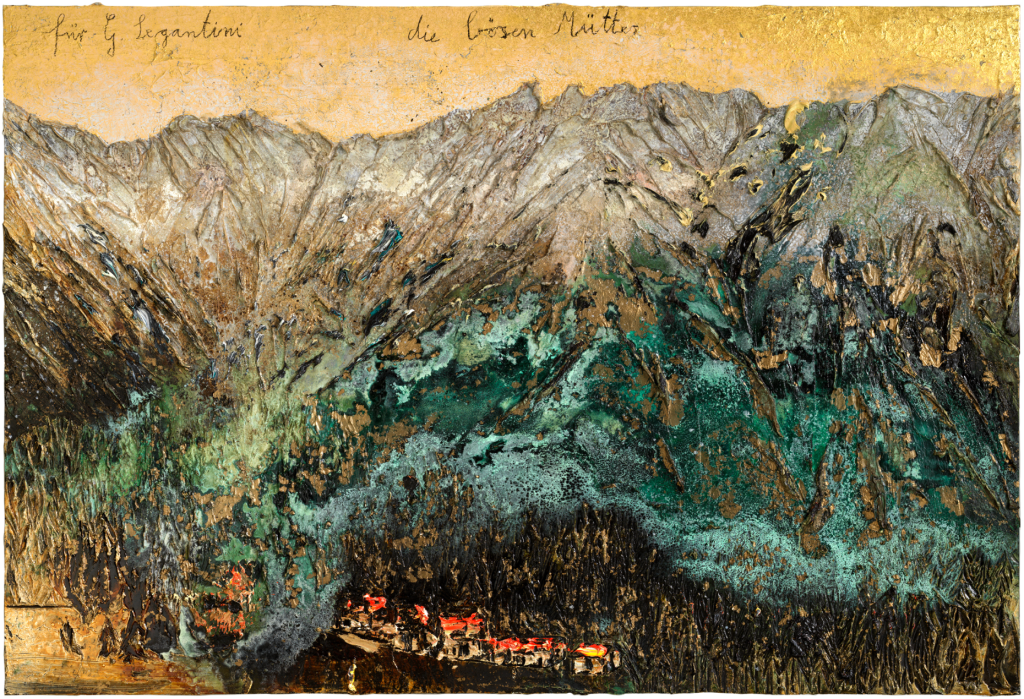

Kiefer’s recent exhibition at Hong Kong’s Villepin Gallery, Golden Age, brings together a series of paintings layered with gold leaf, lead, oil, acrylic, soil, sediment, and various objects, resulting in encrusted topographical landscapes that gleam like golden religious icons. Created between 2020 and 2022, the paintings are thickly impastoed, depicting lofty mountains—a utopian metaphor— set against gold skies.

The landscapes Kiefer presents in this exhibition are, like all his paintings, devoid of people, their absence underscored by a lone bike, or an empty bucket collaged into the composition. Unlike the monumental, architectural canvases for which the artist has become known, depicting dystopian landscapes, the works in this exhibition — a series of alpine landscape paintings and one sculpture— are smaller, though no less densely layered, emphasising material and process, excavating history, and demanding attention and effort to be deciphered. They appear, at least initially, to depict a vision that is optimistic and carefree.

Copyright : © Anselm Kiefer. Photo : Georges Poncet

Paintings in this exhibition display phrases and words scrawled in German, Italian and Náhuatl, across golden skies, above mountains, or across the bottom of thickly painted canvases, helping to translate the iconography embedded in the compositions, and lending the paintings context. The written word is a crucial thread that runs through Kiefer’s works. His creations, including this series, are heavily informed by literature, poetry, and mythology, drawing on iconography and symbolism from sources as diverse as German and Norse mythology, the Kabbalah, alchemy, Aztec, Mesopotamian, and ancient Roman mythology to capture the Manichean conflict that lies at the heart of the human condition and experience. Titles for paintings and sculptures are borrowed from literature and philosophy, and curlicues of words unravel across the surface of paintings, indicating the intimate relationship between the written word and the painted canvas, between painting and poetry.

‘Brunhildes Fel’, scrawled across a painting of a large boulder encircled by autumnal leaves, draws on the Germanic and Norse legend of Brunhilde, Valkyrie daughter of the God Odin, and an important character in Wagner’s epic opera, Der Ring des Nibelungen, which was playing softly in the background during my visit to the gallery. ‘Teocuitlatl’ (2021- 2022), the Náhuatl (spoken by the Aztec and Toltec civilizations) term for gold, which literally means ‘excrement of the gods’ (or holy shit, if you will), is scrawled across the golden canvas of another. It calls to mind El Dorado, the legend of a lost city of gold. The wheat field that stretches out across the foreground of the painting however, alludes to Spanish colonialisation in the Americas and all that it entailed: the plundering of resources (including gold), the exploitation and theft of land for agriculture, the introduction and spread of infectious diseases, slavery and the exploitation and abuse of the indigenous population.

The exhibition’s title and theme draws on German philosopher and cultural critic Ernst Bloch’s writings on the Golden Age and the utopian ideal (Spirit of Utopia, 1918, The Principe of Hope, 1954). Derived from Greek, ‘utopia’ literally translates as ‘no place’, referring to a non-existent society before becoming common parlance for something or someplace imaginary. Western perspectives on utopia as a better, ideal future, extend as far back as Plato’s Republic, one of the earliest conceptions of the idea. Similarly, the term Golden Age— an idyllic period of prosperity, peace and human civilisation—has its roots in Greek mythology, earning a mention in the works of the poet Hesiod and of Plato. As always, Kiefer cycles back through history, juxtaposing mythology and reality, to present a vision of utopia that on cursory glance may appear romantic and idealistic, but in fact strays far from it.

Scratch a little more beneath these impastoed layers of paint, gold leaf and history, and one finds a complex view of the golden age and of utopia. Contradictions, metaphors, and duality are what Kiefer has long played with in his work, and they are layered and pieced together like a puzzle in this exhibition, revealing an ironic post-modern sensibility not without humour. The artist creates tension between hope and despair, the earthly and the divine, chaos and order, in a quest to make sense of the world.

Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, straw, steel and charcoal on canvas

Copyright : © Anselm Kiefer. Photo : Georges Poncet

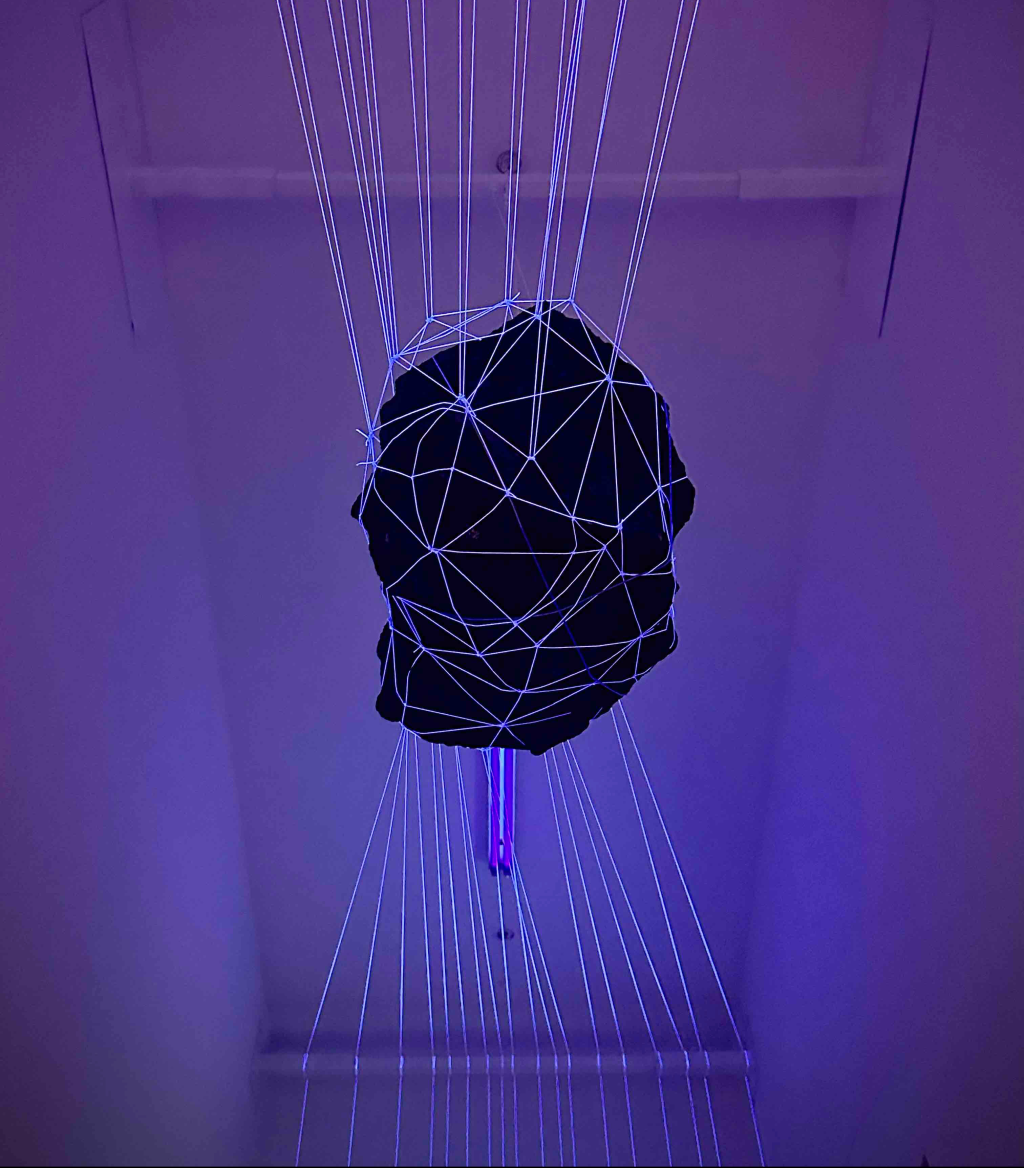

An unorthodox Marxist, and supporter of the Soviet Union and Stalin (before he became disillusioned), Bloch proposed the idea of a utopia grounded in a socialist struggle, not just an escapist fantasy of a non-existent time and place. Yet the socialist struggle and the Russian revolution of 1917 did not result in utopia and liberate workers. In ‘Diamat’, 2020-2022, we see the outcome of Bloch’s utopian socialist hopes. Named after the Marxist theory of ‘dialectical materialism’, or diamat as it was later codified by Stalin, which proposes that progress and change occurs only through (class) struggle and conflict of social forces, the sculpture presents a rickety steel bicycle without handlebars, loaded precariously with a pile of bricks.

Forming the ideological foundation of the Soviet Union, Stalin used diamat as a justification for the establishment of a totalitarian state. The later revolutions of 1989, which brought down the Berlin Wall and led to the collapse of the Iron Curtain, left the ruins of diamat in its wake. Even today, former Communist states are struggling to recover from the legacy of dialectical materialism. Along with the bicycle wheel— symbolic of the cyclicality of life and history—Kiefer often employs bricks as an metaphor for history, symbolizing the ruins of a destroyed city or civilization, or in this case, a political idea. Weighed down by the rubble of the past, the bicycle is unable to move forward.

A prolific writer and influential thinker, Bloch also wrote a series of essays in the 1920s and 1930s that examined the Weimar Republic’s ‘Golden Twenties’, when Berlin became the hub of European avant-garde culture— the ‘golden age’ of intellectual and artistic ambition. Art and literature would illuminate the way forward to utopia, argued Bloch. Except it didn’t. This period of possibilities and hope was cut short by the violent emergence of fascism. As Bloch writes in a later post script in Heritage of Our Times (1935), “The Golden twenties: The Nazi horror germinated in them.” The result was the destruction of hope and a shadow cast across history for decades to come.

Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, straw, bucket and charcoal on canvas. Courtesy of Villepin.

The dark side of utopia, particularly when framed within political discourse, also emerges in ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’ (‘In the Early Dew to the Mountains’), a comparatively minimalist and abstract painting, the surface of which is covered in smooth gold leaf, featuring a small bike perched on the ridge of a textured black patch of mountain. The title ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’ playfully outlines the top ridge of the mountain. Borrowed from a German folk song from the 1920s, (which was taken originally from a Swedish song), the painting and song suggest an idyllic youth in the great outdoors, adventure, and the salvation that can be found in nature. The good ol’ days!

But the song, ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’, also carries echoes of Germany’s Wandervogel, an independent youth movement formed at the beginning of the 20th century. The movement, which had a strong emphasis on German nationalism and reviving Teutonic values, encouraged communing with nature, and contributed to a revival of folk songs in German society, including ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’. By the 1930s, however, the movement was usurped by the national socialist party, which turned hiking into para-militarised nationalism, making way for the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend). The song then made its way into several song collections of the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls, the Bund Deutscher Mädel.

Kiefer understands that reactionary and revolutionary moments in history also have their utopian aspects— the Third Reich, and the Communist Party of the USSR, drew on utopian images and mythology, and refashioned them to serve their political propaganda. Utopia often descends into dystopia. Philosopher Karl Popper suggests that even Plato’s utopian Republic had the hallmarks of totalitarianism and inspired the totalitarian movements of the 20th century. History has shown us that utopia is a flawed social blueprint—it has never quite lived up to its promise.

Kiefer’s vision for Golden Age is not one of saccharine nostalgia for the lost perfection of a gilded ‘(non) past’ or utopia (because utopia does not exist), but a warning. A better world ought to be possible, but many hopes turn out to be illusions—Bloch himself was witness to the failure of hope. If the past—the unmentionable past which Kiefer revisits in his paintings— and the present, have shown us anything at all, it’s that passive hope is not enough. Public imagination and hope can be — and have been—hijacked by empty political slogans and ideology. History informs the present. But, in the “darkness of the lived moment” there is the possibility for humanity to be somewhat redeemed by wisdom and avoid the tragedy and insanity of repeating the same historical mistakes, to confront and learn from the past, rather than resorting to the idealisation of a ‘golden age’ or surrendering to the (false) promises of utopia.

You must be logged in to post a comment.