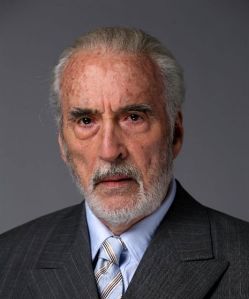

The accolade “cinema legend” is often applied, but not always true. But for Sir Christopher Lee, perhaps my most personally beloved actor, it truly was. Like his best friend and co-star Peter Cushing, he always came across as a true gentleman and a man of formidable wit and intellect. A one-time Special Forces soldier, opera singer, fencer and (seriously) heavy metal singer, Sir Christopher was an inspiration, showing us that if you wanted to record a rock opera in your nineties, who the hell was to tell you otherwise. For those who still only remember him for Dracula, Scaramanga or Saruman, that is no total loss even if it does overlook an astonishingly varied creative career; he was so good in those villainous parts, adding gravitas to glorified pulp, that he casts a long shadow that lesser actors in those genre films will remain in for a very long time.

Born in 1922 in Belgravia, London, the son of a Colonel and a Countess, Lee came to acting young, although opera was originally the love he thought he would pursue foremost. A man borne of privilege, that is sure, but such cultural openings would have been wasted on a man without Lee’s keen mind; he embraced the creative opportunities early. His military career is also notable, including intelligence work in World War II. The latter episodes, he was always silent about, although conversely being very vocal about his adherence to the vow of silence he had made to Her Majesty’s government. In later years, when quizzed about it, Lee would reply, “Can you keep a secret? Well, so can I!”

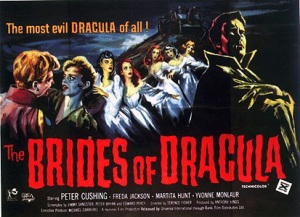

I was vaguely aware of Sir Christopher as a child, but more for his appearances in various swashbuckling romps like The Three Musketeers and its sequels (where his villainous Comte de Rochefort almost out fences all three of the Musketeers) and his turn as Bond villain Francisco Scaramanga in The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). His famous horror appearances remained hidden from my juvenile eyes, until my teens when I discovered Hammer studios’ lurid and imaginative output, beginning with the stylish and engagingly concise adaptation Dracula (1958), re-titled Horror of Dracula for the American market, to differentiate it from Todd Browning’s influential 1931 version with Bela Lugosi . Lee was a reluctant Dracula, at least after the second film of a record nine appearances, always coerced into the part by a guilt trip from Hammer’s producers. Despite this, he is to many people’s mind, the epitome of Bram Stoker’s character, even though he bared little resemblance to Stoker’s descriptions (except in the 1970 non-Hammer Spanish film Count Dracula (1970), where some adherence to Stoker’s text is attempted). He was, however, perfect as a more urbane and sexually potent Dracula, his wolfish grace and grimace making predecessors like Bela Lugosi look almost tame. As Nina Auerbach states in her influential book Our Vampires, Ourselves, each generation gets the vampire they deserve or need, and Lee’s Dracula was perfect for the late ‘50s to the early ‘70s, a period of unprecedented creative and social liberation in society and the arts. Like the time he played the part through, Lee’s Dracula was the shock of the new; a shocking gaudy colour version of what had preceded it. Lee brought something else to his horror roles too, in a time where transient youth trends dominated; he brought a passionate intelligence and love and respect of literature and the arts. Even in the most fatuous of his roles, he brought a seasoned respect for the source material which invariably elevated even the lamest product. Dracula 1972 AD (1972) and The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), his last two Dracula films for Hammer, are the epitome of the kind of bandwagon chasing trash pop culture can sometimes produce, transplanting The Count to a post-Swinging London setting, with miniskirts, pop music and flash car chases. But with Lee in the part, quoting lines from Stoker, each film was far better than it has any right to be. In truth both rank as two of my favorite Hammer Draculas, the latter film coming across like an unexpected fusion of The Avengers (in which he guest starred), The Professionals, Pertwee-era Doctor Who and Quatermass. Lee hated it, but it was a memorable way to bow out of the part.

Cinema’s longest serving Dracula, from 1958 to 1973 ; a record nine films, including seven for Hammer studios.

But he was an actor of far wider range than Dracula, The Mummy or Frankenstein’s Monster, as most fans will tell you. Even within the Horror genre he played a debonair hero (The Devil Rides Out), a charismatic cult leader (The Wicker Man) and comedy (House of the Long Shadows). An actor who communicated as much through his presence, gestures and saturnine expressions than that deep resonant voice, Christopher Lee was arguably the last of a type of actor we may not see again, at least for a very long time. A modern trained actor would surely be accused of parody or sheer ham if they attempted to replicate what Sir Lee did regularly with such dignity and panache. A combination of talent and pure charisma allowed something special to come from Sir Lee’s efforts, that just cannot be taught.

Long term viewers couldn’t help but feel pleased when, after a decade or so of increasingly fatuous parts (Gremlins 2, while not a career bottom, is no masterpiece), he quietly returned, at first in significant guest roles in such imaginative fare as BBC TV’s Gormenghast adaptation or Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow (a blatant Hammer tribute), and then more noticeably, as pivotal villain Saruman in the epic Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001- 03), and as the Machiavellian Count Dooku in parts two and three of George Lucas’ Star Wars saga (2002-05). Think of those films, and Christopher Lee’s presence lifts each film’s quality just by his presence. Even in Peter Jackson’s beloved interpretation of Tolkien’s Rings trilogy, the ultimate corrupt evil needed a face and a voice, and who else better than a consummate veteran professional and Tolkien expert? When Hammer studios returned, and began to once again produce quality horror, Christopher Lee returned to the fold, appearing in The Resident, his first Hammer for 35 years. But it was his role as the founder of modern Pakistan, Mohammed Jinnah, in the 1998 film Jinnah, which gained Lee his most consistent critical praise. Sir Lee himself thought of it as his most important film. The Wicker man may have been his favourite film, but the role he felt had made a difference was Jinnah. I can’t recommend it enough, and adds weight to the argument that Lee was underrated as an actor (or more accurately, the studios took him too much for granted, accepting his wide range as a matter of fact, but rarely utilizing it as much as they should have).

His recall and verbose accounts continued to the very end; Lee was an excellent raconteur, often relating stories from as far back as his time served in the war and early film roles such as Corridor of Mirrors (1948), where he was directed by future Bond helmsman Terence Young. He also had excellent manners, and was a gentleman in every sense. An often shared story relating to the first private screening of this beloved The Wicker Man, led to arguments over the ‘butchering’ of the film. Lee went to see the new head of British Lion, to find out what his studio had done to the film. Lee commented that he could immediately guess the manner of man he was dealing with as “he didn’t even stand up for my wife”.

Anecdotes like this are always amusing, particularly as Lee seemed happier to send himself up for an ungratuitous chuckle in later years (at a seminar in Dublin in 2011 he was asked about Dracula. Quick as a flash, Lee replied with faux confusion: “Who??”). But Lee took his craft seriously, and from the way he spoke about family and friends, he took his love and admiration for them seriously too. His advice on the longevity of his marriage was simply, “marry somebody wonderful”, and his heart breaking eulogy to Peter Cushing leaves no one in doubt to the deep friendship between to the two men.

Not just a great actor, and a true renaissance man in general, Lee is still an inspiration to those who value manners and respectful intellect alongside a creative path. Sir Lee worked until the very end, because that’s what he loved to do, and he died as he wished: “with my boots on”. I speak for millions when I say, he will be missed. Few artistes deserve as much praise as I’ve just given him, in a world where other more quiet talents could save us from war, disease and other more perils. But through creative endeavor we often have an example in conduct that lifts us from life’s gloom. A consummate professional, and a larger than life presence who entertained and sometimes shocked (but never gratuitously or without scruples) Sir Lee was rightly a treasured talent. I also fear Christopher Lee was the last of his kind, and sadly we may not see his like again.

One of the few actors I genuinely wish I’d met, and as the love of a fan can last a lifetime, I’ll probably always wish it. Sir Christopher, thank you.