On a cool and sunny fall day in Hartford, ten thousand people jammed into Bushnell Park with one goal: to stop the war in Vietnam. As the single largest protest of its kind in the city’s history, October 15, 1969 was historic. And the thousands who marched to downtown Hartford were only part of the 90,000 Connecticut residents taking part in peace actions in dozens of cities, towns, schools and churches against a war that had already taken a deadly toll on two continents. It was called Moratorium Day–a nationwide suspension of normal activity by two million people to focus on the war—and it was the result of thousands of small courageous actions by ordinary people, many of whom decided to challenge their government for the first time.

Moratorium Day was the brainchild of former staffers for the 1968 Eugene McCarthy Democratic presidential campaign (McCarthy lost to Hubert Humphrey, who lost to Republican Richard Nixon, who claimed to have a “secret plan” to end the Vietnam War). The organizers’ plan was to suspend business as usual in order to discuss, debate and protest the increasingly unpopular war. It was to start with one day in October and then multiply: two days in November, three in December, and so on until the entire country focused only on the war. In the end, the Moratorium made history, even if it did not succeed as a long-term national strategy.

Building toward critical mass

Protests against the Vietnam War had been organized as early as 1963, but these were largely confined to a few college campuses and traditional Hiroshima remembrance activities led by Quakers. By 1965, a national demonstration called by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) drew 25,000 to Washington, D.C. The turnout was small by today’s standards, but it was the largest protest ever held at the time against an American war. Over the next few years hundreds of college campuses exploded with teach-ins, draft resistance and administration building occupations. The growing anti-war agitation had convinced a sitting president, Lyndon Johnson, that he had no future in politics. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King had connected the dots between racism at home and militarism abroad. The antiwar movement derailed the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. America’s working class, Black and white, was painfully aware of the ever-increasing costs of war and in fact, one famous survey found that workers’ opposition to the war was greater than that of the middle class.

Protests against the Vietnam War had been organized as early as 1963, but these were largely confined to a few college campuses and traditional Hiroshima remembrance activities led by Quakers. By 1965, a national demonstration called by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) drew 25,000 to Washington, D.C. The turnout was small by today’s standards, but it was the largest protest ever held at the time against an American war. Over the next few years hundreds of college campuses exploded with teach-ins, draft resistance and administration building occupations. The growing anti-war agitation had convinced a sitting president, Lyndon Johnson, that he had no future in politics. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King had connected the dots between racism at home and militarism abroad. The antiwar movement derailed the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. America’s working class, Black and white, was painfully aware of the ever-increasing costs of war and in fact, one famous survey found that workers’ opposition to the war was greater than that of the middle class.

But beyond campus and big city demonstrations, opposition to the war had not made its presence felt in middle America, the constituency President Nixon considered his base. In November, 1967 a national poll found that only 10% of Americans thought the U.S. military should be pulled out of Vietnam. A Connecticut poll in April, 1969 did not even ask about the war. Instead, results showed the public was most concerned about the “lack of respect for authority by young people.”

An April 26, 1969 anti-war rally in Bushnell Park drew barely a mention in the local press. But the anticipation created by the Moratorium inspired a Hartford newspaper to rent an airplane so it could capture images of the thousands of marchers who snaked down Albany Avenue towards Bushnell Park.

Digging in at the grassroots

Local organizing for Moratorium Day was a massive undertaking. Volunteers leafleted hundreds of neighborhoods, businesses and schools. Churches and synagogues announced the event during services. Veteran folk singer Pete Seeger and farmworker union leader Cesar Chavez were both in town for their causes and urged supporters to join upcoming peace events (Chavez noted that the Defense Department’s spending on grapes had jumped 800% since his union’s boycott of the fruit had begun.) Trinity College students urged the administration to shut down the school for the 15th. The president refused, but most classes were cancelled anyway.

In Hartford, West Hartford and Meriden, organizers worked with local businesses to close their shops during the middle of the day. At least 60 businesses expressed their support.

Momentum around the state grew and in many places support for the Moratorium was surprisingly deep. Two-thirds of Hartford’s Bulkeley High School students skipped school to attend the Bushnell Park demonstration. In Stamford, Norwalk, Waterbury, Windsor and East Hartford students and their teachers planned assemblies during school hours to discuss the war and its impact on their lives. Town greens were rally sites in Wethersfield, Bridgeport, Simsbury, and Farmington. Anti-war sentiment found its way into the streets with marches through the town centers of West Hartford, New London, Bristol, New Britain, Windsor Locks and Greenwich. In many places activists held multiple events, combining their tactics and thinking up new ways to focus attention on the deadly impact of Vietnam policy.

In Willimantic, protestors marched through downtown and stopped at the local IRS office to highlight the fact that “billions of dollars are spent on Vietnam each month, while national housing, medical and educational programs remain unresolved.”

In Goshen, authorities refused Moratorium backers’ request to plant a “peace tree” on public property so they found willing landowners who hosted the event instead.

A number of town councils and boards of education were challenged to take a stand on the war. Most refused, as did Enfield where the vote was 5-2 against an immediate withdrawal of all US troops, even as marchers paraded outside the Council chambers. But in Westport, the Representative Town Meeting backed the pullout of troops, and both the Mansfield and Manchester Democratic town committees passed resolutions against the war.

The Moratorium had its detractors, of course. U.S. Senator Thomas Dodd, a Democrat, stated that immediate withdrawal was “immediate surrender.” Congressman Thomas Meskill said that he hoped October 15th would be seen as support for Nixon and his policies (the next year, Meskill was elected Connecticut’s Republican governor). New Britain’s Mayor Paul Manafort ordered 250 American flags to be flown in the city to protest the peace actions.

Veterans speak out

The local American Legion and VFW condemned the protests, arguing that dissent would only endanger U.S. combat troops. But not all soldiers agreed. Many Vietnam veterans saw the Moratorium as a time to finally speak out publicly against the war they had survived.

Dozens of Vietnam veterans joined the Hartford rally. One young vet who had been wounded in the legs and chest told a newspaper that he marched because “you find you’re not fighting for anything, you’re just fighting to save your life.” Vietnam was a suicide mission, he said.

Forty vets at Mattatuck Community College in Waterbury made their anti-war sentiment known during a school event. In Enfield, Navy veteran Richard Howland and WWII veteran Eugene Sweeney addressed the local peace rally. Veteran George Smith and former Marine captain Newbold Morris addressed the West Hartford crowd. Dean Erickson told protestors in New Britain “over there I was shown that the Vietnamese do not want foreign domination, and that’s why I’m here now.”

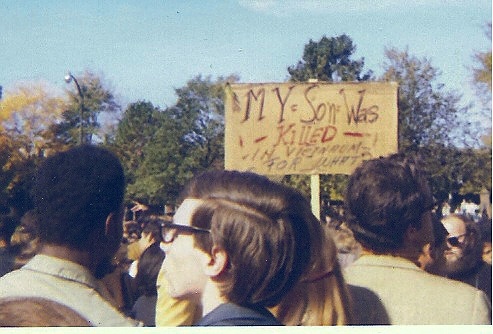

For some of those who enlisted or were drafted, the Moratorium came too late. Bloomfield’s Barry Jackson was one of the many killed in the war. His father Allen attended the massive Hartford rally with a hand-made sign that read “My son was killed in Vietnam- For what?” Mr. Jackson’s son had won a number of medals, “but these medals don’t make up for his life.” Barry should not have gone to Vietnam “because it’s an illegal war.” Although his protest was too late for Barry, Allen Jackson thought his presence might help others.

Ten thousand American troops were killed in 1969. Hundreds of them came from Connecticut. During the week of the Moratorium, the fatalities grew: Marine Pvt. Richard Stolarun, 19, of New Britain, died of his wounds on October 12th. Lt. Thomas Frazier, Jr., 20, of Granby and Army Pfc Charles Bachman of Norwalk were both killed in action the next day. Mr. and Mrs. Norman Manning received their son James’ Silver Star that week. He had been killed in July after having won the Purple Heart and Bronze Star. On October 16th, Pfc James Dufault of Moosup was killed in combat. Dufault became the 466th Connecticut resident to be killed in Vietnam.

The consequences of standing up

Joining the Moratorium was a big deal for thousands of state residents, young and old, who  had never before attended an anti-war protest. One inhibitor for these first-timers was fear: fear of looking foolish, of being labeled unpatriotic, of the unknown. And in a few cases there were consequences for speaking out. In Farmington, thirteen students faced suspension for leaving school without proper parental permission. Teenagers Gary Marone and George Cavanna were arrested by Glastonbury police for wearing the American flag as headbands. Hartford college and high school students were busted for plastering Moratorium leaflets on buildings or for spray-painting “WAR” on Stop signs.

had never before attended an anti-war protest. One inhibitor for these first-timers was fear: fear of looking foolish, of being labeled unpatriotic, of the unknown. And in a few cases there were consequences for speaking out. In Farmington, thirteen students faced suspension for leaving school without proper parental permission. Teenagers Gary Marone and George Cavanna were arrested by Glastonbury police for wearing the American flag as headbands. Hartford college and high school students were busted for plastering Moratorium leaflets on buildings or for spray-painting “WAR” on Stop signs.

Eight Bloomfield elementary school teachers were reprimanded for taking their kids off school grounds for an impromptu march of their own. The brief event was a civic lesson, the teachers explained, but some parents were outraged. Robert Bligh complained that his two daughters, aged 8 and 10, should not have been part of the protest. According to their mother, the girls challenged Bligh when they got home: “What’s the matter? Don’t you believe in peace?” they asked their father.

Sixty Naugatuck High School students skipped school and gathered at the American Legion field on their way to the New Haven rally. They scattered when spotted by the police. The cops gave chase but only a few of the runaway activists were caught.

Many around the state joined the protests, however, with no negative results. At East Windsor High School, about 60 students decided that the officially-sanctioned assembly was too tame, so they walked out of classes. Several teachers and the principal tried to persuade them to return, without success. A local state trooper was summoned, but he had no luck either. Students told him that it was their generation fighting the war, not his. One high school girl said that the planned in-school Moratorium activities were not strong enough to show how they felt about “this terrible war.”

War, race, and gender

The Moratorium’s focus was Vietnam, but Connecticut cities were still seething with unrest and rebellion. Hartford experienced this anger with riots in July and September, 1967, and again in April, 1968 after the assassination of Dr. King. Student organizers determined that the economic and political oppression experienced by the African American community could not be ignored on October 15th. The march toward Bushnell Park began in West Hartford on the University of Hartford campus. The route could have easily avoided the Black areas of the city by traveling down Prospect Avenue, passing by the Governor’s mansion and through the comfortable West End. But instead 6,000 students marched down Albany Avenue through Hartford’s poorest neighborhoods, picking up support as they went.

Wilber Smith was there to greet the students when they arrived. Smith was a militant African American leader who had called for a civilian police review board after incidents of police brutality in 1968. This year he was running for Mayor on the newly-formed Liberal Party ticket. He called the Vietnam war “insane” and told the cheering crowd in Bushnell Park “we must not lower the sound of our protest until the administration’s deeds match their empty rhetoric.”

Larry Babatunji told Central Connecticut State College students that it was wrong for Black men to fight in a war for “a decrepit, racist country.” In Middletown, Ed Saunders of the African-American society marched with the sign “No Vietnamese ever called me nigger,” a phrase attributed to boxing superstar and draft resister Muhammad Ali. Black Panther Doug Miranda told 2,500 UConn students and faculty “I don’t fight white racism with black racism. I fight racism with people’s solidarity. I fight racism the same way the Vietnamese people fight racism.”

In New Haven, the rally stage was dominated by white establishment politicians. Yale junior Glenn deChabert fought his way to the microphone to make the connections between racism and war. The rally organizers did their best to stop him, even shutting off the sound system when deChabert began to talk. But people in the crowd chanted “let him speak!” and he did. The Black Student Alliance leader addressed the crisis in New Haven’s neighborhoods, including “brutal and murderous police policies.” DeChabert challenged Yale and the Mayor to solve the city’s economic problems. “Peace is the attainment of justice for Blacks,” he told the New Haven crowd.

Women were barely represented on the Moratorium stages around the state, although there were a few exceptions. Ella Grasso, then Connecticut’s secretary of state, was part of the establishment roster in New Haven. Marge Swann of Voluntown’s Community for Non Violent Action (CNVA) led a civil disobedience workshop in Storrs. Women played critical roles in the hard organizing work that made the day a huge success. Shirley Epstein was statewide coordinator for the Moratorium. Mary Lou Mayo and Naomi Golden pulled Wethersfield’s peace activities together. West Hartford women made sure local businesses closed their doors on October 15th.

The Anti-warriors

Local activists who were part of the Moratorium in 1969 have clear memories of that day. Mims Butterworth, now 97, read the names of the Vietnam war dead with her husband Oliver in front of 2,500 West Hartford residents. She remembers being most proud of the Conard High School students who marched with her, despite being harassed by student athletes and their coach. Mims had been an anti-war McCarthy delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention, and would go on to join the 1971 peace delegation to the Paris Peace talks.

John Murphy was a junior at East Catholic High School in Manchester. Unlike other schools, there was “no getting permission slips” in order to join the Moratorium activities. John and about eight other students skipped school and traveled by bus to the Hartford rally. Today he is a leader of the Connecticut Opposes the War coalition.

Hartford’s Dave Ionno, who is currently a leader of Veterans for Peace, was a young “army brat” in Washington State during the Moratorium. He watched anti-war marches with his family on television that fall. He enlisted in November. Dave served a year in Vietnam. When he returned, changed forever by the experience, Dave’s first Veteran’s Day march was with Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Jeremy Brecher was a regional SDS organizer in the Northwest, and is now a Connecticut-based activist and historian. He critiqued the limitations of the Moratorium in a widely distributed essay in Liberation magazine in December, 1969. Jeremy saw some anti-war activists’ turn toward electoral politics or street violence as distractions from the real work of building a movement powerful enough to stop the war. He called for future activities to be shaped more like a general strike against the war, based in workplace organizations.

The draft resister and the antiwar prosecutor

Forty years after the historic October 15th Hartford protest in Bushnell Park, David Mitchell was shocked to learn that the rally’s moderator was Jon O. Newman, a U.S. District Attorney. Newman was the man who helped send Mitchell to prison for resisting the draft.

Mitchell had lived in New Canaan and attended Brown University before dropping out. In 1961 he joined Polaris Action, a campaign that used nonviolent direct action against nuclear submarines built in New London. Mitchell and others variously swam, sailed and rowed out to the subs to interfere with their launching. By the time he was eighteen Mitchell had decided to refuse induction when called up by his Connecticut draft board. He based his opposition on the Nuremberg principles, arguing that America’s Vietnam policy violated international law and treaties the United States had signed. Therefore, Mitchell reasoned, joining the Army only contributed to the war crimes taking place in Southeast Asia.

Mitchell was arrested for failing to show up to his Draft Board and for refusing to register as  conscientious objector. His first trial took place in New Haven in September, 1965. The trial was a disaster: his attorney refused to follow Mitchell’s carefully-planned defense strategy, the presiding judge was extremely hostile, and his bail was set outrageously high. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed his conviction, leading to second trial in 1966 in which he was prosecuted by federal prosecutor Jon Newman. David Mitchell received a five-year prison sentence; he served two years at the Lewisberg federal penitentiary from February 1967 to February 1969.

conscientious objector. His first trial took place in New Haven in September, 1965. The trial was a disaster: his attorney refused to follow Mitchell’s carefully-planned defense strategy, the presiding judge was extremely hostile, and his bail was set outrageously high. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed his conviction, leading to second trial in 1966 in which he was prosecuted by federal prosecutor Jon Newman. David Mitchell received a five-year prison sentence; he served two years at the Lewisberg federal penitentiary from February 1967 to February 1969.

Newman was known in Connecticut circles as something of a liberal. He debated William F. Buckley on the issues of the day and later distinguished himself as a judge when he struck down the state’s anti-abortion law. By 1969 his opposition to the Vietnam War led him to publicly join the Moratorium. The next year he helped organize a group of professionals and businessmen against the war and briefly ran for Congress on a peace platform.

When confronted by a reporter about the key role he played in sending David Mitchell to jail, Newman replied that he saw no contradiction between that and his emcee role at the Hartford Moratorium. If he had to do it all over again, Newman said, he would still prosecute Mitchell. “He felt you can call upon the courts to rule upon the validity of our foreign policy and I don’t think you can,” Newman stated. He admitted that even during Mitchell’s trial in 1966 he harbored doubts about the war.

David Mitchell remembers Newman as “a decent sort of guy” who, after the guilty verdict, asked the defense attorney if Mitchell might shake his hand. Still, the draft resister contrasts Newman to the Yale legal scholar and civil libertarian Thomas Emerson who “walked into the New Haven courthouse and put up his home as collateral” in order to help Mitchell make bail. “I had never even met him and he did this for me,” Mitchell recalls.

Today Newman serves on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. David Mitchell (despite his felony conviction) is an attorney in New York and still an anti-war activist. He has most recently assisted Lt. Ehren Watada, an infantry officer who in 2006 refused to deploy to Iraq. Like Mitchell, Lt. Watada refused deployment on the grounds that the Iraq war was immoral and illegal, and that to participate in it would make him complicit in war crimes. Watada’s prosecution ended in a mistrial and his request to leave the Army was refused until he was finally discharged on October 2, 2009.

Lessons for today’s antiwar movement?

It’s tricky to draw direct parallels between events separated by decades and circumstances. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan sent millions of people to the streets in a much shorter time period than it took to mobilize against the Vietnam War. All protests, even massive ones, are dogged by impossible expectations: if they don’t immediately achieve their objective they are seen as having failed. In fact, the Trinity College student newspaper editorialized in 1969 that the Moratorium was a failure because President Nixon seemed to ignore the millions who marched.

In hindsight we now know that anti-war activity, in particular the October Moratorium (and its Washington counterpart of 750,000 protestors in November), played an important role in curbing Nixon’s Vietnam policy. Seymour Hersh confirms this in The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. The investigative reporter and Pulitzer Prize winner asserts that the administration’s intention to escalate the war was thwarted in large part by the massive numbers generated by Moratorium activities. “Operation Duck Hook,” as the unsuccessful secret plan was called, was designed as a “savage” and “brutal” response (Kissinger’s words) that included the use of nuclear weapons, land invasions of North Vietnam, and renewed saturation bombings in the South.

Although the Moratorium campaign could not be sustained as its founders had envisioned, anti-war organizing continued and grew. The 1970 invasion of Cambodia and the murders of students and Kent State and Jackson State ignited a nationwide student strike in May with four million students participating. In 1971, 13,500 were arrested while attempting to stop business as usual in Washington, D.C. The majority of the America population turned its back on Nixon and his war policy.

* * * * * *

On October 15, 1969, a small group of church people led by the Reverend Herbert Ackerly and Mrs. Laurence Morrison stood quietly in front of Hartford’s Old State House. They had been there faithfully each Wednesday for three years. The group called it their “vigil of conscience.” On Moratorium Day, their patience was rewarded: six thousand marchers on their way to Bushnell Park paraded past the silent vigilers, and cheered.

Excellent piece Steve. I was one of the 25,000 in DC in 1965. I left Hartford in 1966 after graduating high school for Madison WI where the ant-war movement grew like wild-fire. I returned to Hartford in 1970. The stories I heard about the movement in Hartford, and its surrounding towns, were inspiring. There is a remarkable history of left and progressive action in Hartford, especially from the early and mid 60s.

Hank, you should comment on all the writing here . Not saying you’re old, just that you are a big part of Hartford movement history!

Thanks, Steve, for the wondeful story and widening a New Haven-centric perspective. I hope others take up the baton and write their own city’s stories.