Would you want to be a Freemason?

- Published

- comments

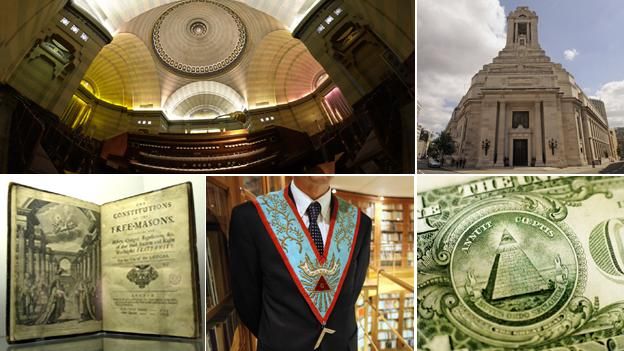

Dogged by conspiracy theories, Freemasons insist theirs is a modern, open organisation. But can this male-dominated body cast off its secretive image and win over a sceptical public?

They designed the pyramids, plotted the French Revolution and are keeping the flame alive for the Knights Templar. These are just some of the wilder theories about the Freemasons. Today they are associated with secret handshakes and alleged corruption in the police and judiciary.

But dogged by this "secret society" image, the Freemasons have launched a rebranding exercise.

On Friday, the United Grand Lodge of England, the largest Masonic group in Britain, publishes its first independent report. The Future of Freemasonry, researched by the Social Issues Research Centre, aims to start an "open and transparent" discussion ahead of the group's tercentenary in 2017.

Nigel Brown, grand secretary of the United Grand Lodge, says it's time to banish the reputation for secrecy. "We're being proactive now. It's essential we get people's minds away from these myths." For instance, there is no such thing as a secret handshake and professional networking is forbidden under Masonic rules, he says.

Even this is disputed. Martin Short, who wrote about the Masons in his 1989 book Inside the Brotherhood, says the handshake is real. "If you meet a middle-ranking police officer, you'll suddenly find this distinctive pressure between your second and third fingers. The thumb switches position and you feel that someone is giving you an electric shock."

The report for the most part dodges such controversy, surveying members and the wider public on Masonic themes such as male bonding, charitable work and ritual. It argues that members value the community of Freemasonry and that outsiders are largely ignorant of how the organisation works.

With 250,000 members in England and Wales and six million around the world, they are a minority, albeit one associated with the levers of power. The first US President, George Washington, and another leading American revolutionary, Benjamin Franklin, were Masons. Today a significant proportion of the Royal Household are members, and the Duke of Kent is grand master of the United Grand Lodge of England.

Masonic rules demand that members support each other and keep each others' lawful secrets, which has led to fears of corrupt cliques developing.

It's nothing new, says Observer newspaper columnist Nick Cohen.

Ever since the 1790s Masons have been "whipping boys" for global conspiracy theorists, he argues, adding that after the French revolution, Catholic reactionaries were looking for a scapegoat and the Jews - the usual target - were too downtrodden to be blamed.

It was the Freemasons' turn and the narrative of a secret society plotting in the shadows has never gone away, says Cohen. "You can draw a straight line from the 1790s onwards to the Nazis, Franco, Stalin right up to modern Islamists like Hamas."

The charter of Hamas - the Islamist party governing Gaza - states that the Freemasons are in league with the Jews and the Rotary Club to undermine Palestine.

These theories are "clearly mad", says Cohen, but attacking the Masons has become a staple for anyone suspicious of a New World Order.

There's also the sense that Freemasons are "weird", says James McConnachie, author of the Rough Guide to Conspiracy Theories.

Initiations include rolling up one's trousers, being blindfolded with a rope round one's neck, and having a knife pointed at one's bare breast. "They offer a progression to a higher level of knowledge," McConnachie says. "It's alluring and cultish."

Grand secretary Brown argues that the initiations are allegorical one-act plays. They give people "from all walks of life" the chance to stand up in front of an audience, conquer their fears, and make friends, he says.

"People don't associate fun and enjoyment with Freemasonry but it's the common thread for us. It's about camaraderie and making lasting friendships."

Another vexed issue is its male-only image. There are women's orders in Britain with 20,000 members, but Freemasonry is overwhelmingly male. The UGLE does not recognise or approve mixed lodges.

The report talks of a "quiet revolution". But some information should be withheld from public view, Brown says. "Keeping a bit of mystery is good news. If people joining know absolutely everything, where would the excitement be?"

The Masons are walking a difficult tightrope, says brand consultant Jonathan Gabay. For the rebrand to be effective, they have to demonstrate they are serious about being open and transparent. And yet, in the process, they risk alienating members who value the "cachet" of secrecy and tradition, he says.

People join the Masons not because it is a community group raising money for charity but for its "snob factor" and history, argues McConnachie. If this is overtaken by a transparent, inclusive approach then the organisation would be indistinguishable from many other dining clubs. "You'd have to ask - why would you want to be a Freemason rather than a Rotarian?"

Distrust remains strong. Last year, the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams controversially named a Freemason as the next Bishop of Ebbsfleet. He had previously said that Freemasonry was "incompatible" with Christianity. In August 2010 it emerged that a new national Masonic lodge had been set up by senior police officers.

Former Home Secretary Jack Straw tried to address the issue of Freemasons working in the criminal justice system. In 1999, new judges were required to publicly disclose whether they were Masons.

But after a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights, the requirement was dropped in 2009. Police officers have a voluntary requirement to disclose - but only to their superiors.

Researching his book in the 1980s, Short found that "corruption in the police was enhanced and shielded by the Masonic lodges."

It's difficult to know whether anything has changed as the Freemasons do not make their membership list freely available, he says. Brown responds that to do so would breach data protection rules.

Given all the suspicion, it's hard not to feel sorry for Freemasons, says Cohen.

"Researching them, you do become rather sympathetic. If people want to say Freemason lodges are nests of corruption then fine. But they've got to prove it. It's no good just saying it."

However, there is something amusingly peculiar about Masonic ritual. It is this rather than the historical baggage that is their biggest obstacle to getting a fair hearing, he argues. "Rolling your trouser leg up is quite funny. If they do want to rebrand then perhaps they should drop the trouser leg rolling."

- Published14 March 2012