The man who created the ultimate alien

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenHR Giger drew on demons of the past to provide an unsettling vision of the future. As Taschen publishes a new book of his work, the writer and critic Andreas J Hirsch looks at how the Swiss artist merged human and machine in his haunting images – giving expression to the collective fears of his age.

In the spring of 1978, having just turned 38 years old, the Swiss artist HR Giger jotted these lines in his diary: “May 18, 1978. Work on the film is in full swing. The construction of the spaceship is almost finished. It looks good. Small models of the landscape and the entrance area of the spacecraft were made. The people who built these have no clue about my architecture. I said that they should get bones and build a model with plasticine…”

Alien beginnings

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

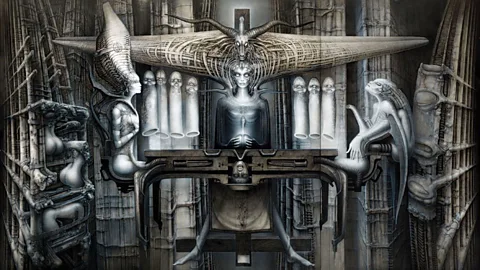

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenAt that time, HR Giger was already a successful painter whose bleak visions in a style that he termed biomechanics were widely distributed: in the form of popular poster editions that appeared in the late 1960s; in the large-format illustrated book Necronomicon, which he designed himself; and on album covers such as Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s 1973 release Brain Salad Surgery. But the project he was now working on would make him both a worldwide cult figure and an Oscar winner. Director Ridley Scott had hired Giger to create the monster in the movie Alien. So the artist went to the Shepperton Film Studios near London to realize his designs for the world of the alien with his own hand.

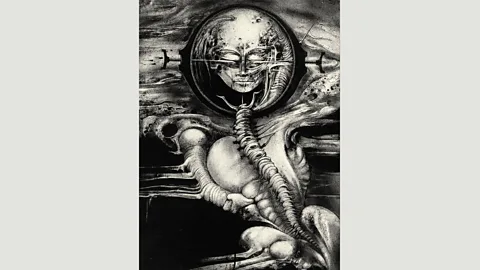

One painting had immediately convinced Scott to get Giger involved in shaping the alien creature: Necronom IV (1976). It shows in profile the upper body of a being with only remotely humanoid traits. Its skull is extremely elongated, and its face is almost exclusively reduced to bared teeth and huge insect-like eyes. Hoses extend from its neck and its back is dominated by tubular extensions and reptilian tails. In order to turn this painted creature into a monster for a movie, the artist had to submit it to a complex transformation. Giger developed a complete “natural history” of the alien based on the screenplay, which ultimately produced the final monster of the film. The process results in a unique mixture of fascination and disgust. Giger’s monster represents a turning point in science fiction and horror movies, to which Alien brought a deadly lifeform from space that had never been seen before.

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenThe myriad traces that Giger’s work has left in so many different areas – painting and film, album covers and tattoo culture, as well as in the genres of science fiction and fantasy – make it like a Rosetta Stone combining several languages that still have to be decrypted. A work that is so densely populated with archetypes and beings from a post-human future, which is well beyond accepted notions of reality and which is so rich in symbols, shapes, and themes from occult traditions, also calls for a reading that includes interpretations from the fields of alchemy, astrology, and magic. The diversity of the readings of these archetypal themes could easily fill a whole library – a ‘Bibliotheca gigeriana’ – on the draftsman, painter, sculptor, filmmaker, and designer HR Giger.

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenHR Giger was born in 1940 in the small town of Chur in the Swiss canton of Graubünden and reports from his childhood already hint at the themes that would determine his later life: in the flat of his parents’ house, where his father also had a pharmacy on the ground floor, he built a ghost train. His target group was mainly girls, in whom little Hans Ruedi showed an early interest. While the others were at church on Sunday mornings, he headed for the basement of the local museum to look at the mummy of an Egyptian princess on display there and stood beside her in a mixture of horror and fascination. When a pharmaceutical company gave his father a human skull, the son took it for himself and pulled it behind him through the streets of Chur on a string.

The birth of biomechanics

Giger’s early work deals very directly with the collective fears of the time. The world had just narrowly avoided a nuclear war over the stationing of Soviet nuclear weapons on Cuba, and in neutral Switzerland, which was working on its own nuclear weapons program, the very real possibility of a nuclear apocalypse was omnipresent. In several of his works, Giger designed a post-apocalyptic scenario showing the situation after a nuclear war. Other hotly debated issues such as the threat of global overpopulation and the advancing mechanization and automation of many aspects of life also found their way into his work.

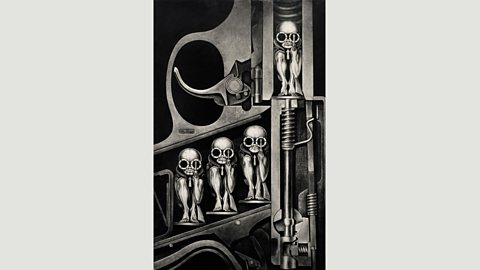

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenAtomkinder (Atomic Children, 1967-68) shows three post-human figures in a stylized artificial landscape. The entire upper half of the picture is filled with an atomic ‘sun’, in front of which two one-legged beings loom. Giger is putting mutation, a long-term consequence of nuclear radiation at the genetic level, at the heart of the image. The two figures almost look like Siamese twins, but they are separate beings who touch each other only at a point of their backs because they need each other to walk upright. They no longer have arms, but masks and tubes leading away from them have become integral parts of their bodies. The tubes lead into the bases of their spines, which are open as if the figures were already on the autopsy table.

Little flesh encases their skeletons, and antenna-like projections stick out from their skulls. A third entity, barely a torso with feet, is sitting on the ground, a hose leading from his back to an opening in the floor. The big nuclear sun has numerous protuberances radiating in all directions. One of them runs into a tube such as the protagonists have.

This tube is either disappearing into the ground or possibly into a fourth creature that we can only discern rudimentarily. The two nuclear children that dominate the picture are looking in different directions. There is no sign of panic or post-apocalyptic despair – the nuclear children are clearly way beyond such emotions. The surface of the earth, if this is what it is about, has been abstracted into pure geometry: there is no longer any landscape that we might find familiar.

HR Giger/Courtesy of Taschen

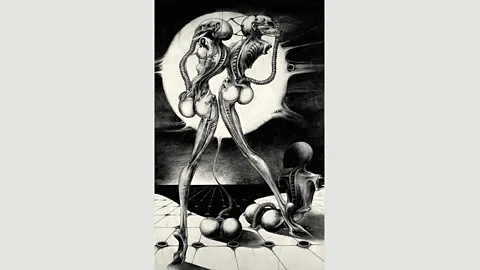

HR Giger/Courtesy of TaschenThis is where HR Giger developed what he would later call his ‘biomechanical style’: a fusion of biological and mechanical components and man and machine on both a factual and a metaphorical level. This visionary anticipation of the later phenomena of cyberculture, in particular the figure of the cyborg, goes way beyond the idea of using technology to compensate for the deficits of the human race. The artist has created a new form of existence, which has no utopian features but is rather portrayed with dystopian grimness.

At the same time, however, Giger himself has described biomechanics as a “harmonious fusion of technology, mechanics, and the living creature”. Because of the oppressive and threatening scenes, this element of harmony may strike an odd note, but it is created by the peaceful dozing that distinguishes his characters. Their apparent calm and balanced state alludes to an underlying concept of beauty that shares nothing with the premodern aesthetics of fantastic art, but is quite at home in a mechanistic and war-hardened modern age. Giger has repeatedly stressed that it would be wrong to see only the terrible things in his paintings because they contain just as much of the elegance that has always been important to him. Whatever their specific forms, horror and beauty are inseparable in HR Giger’s work, just like the dread and fascination that accompany them.

Andreas J Hirsch is a photographer, writer, and curator based in Vienna, Austria, where he has curated exhibitions on HR Giger’s work. This is an extract from an essay he has written for a new book on Giger, published by Taschen.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.