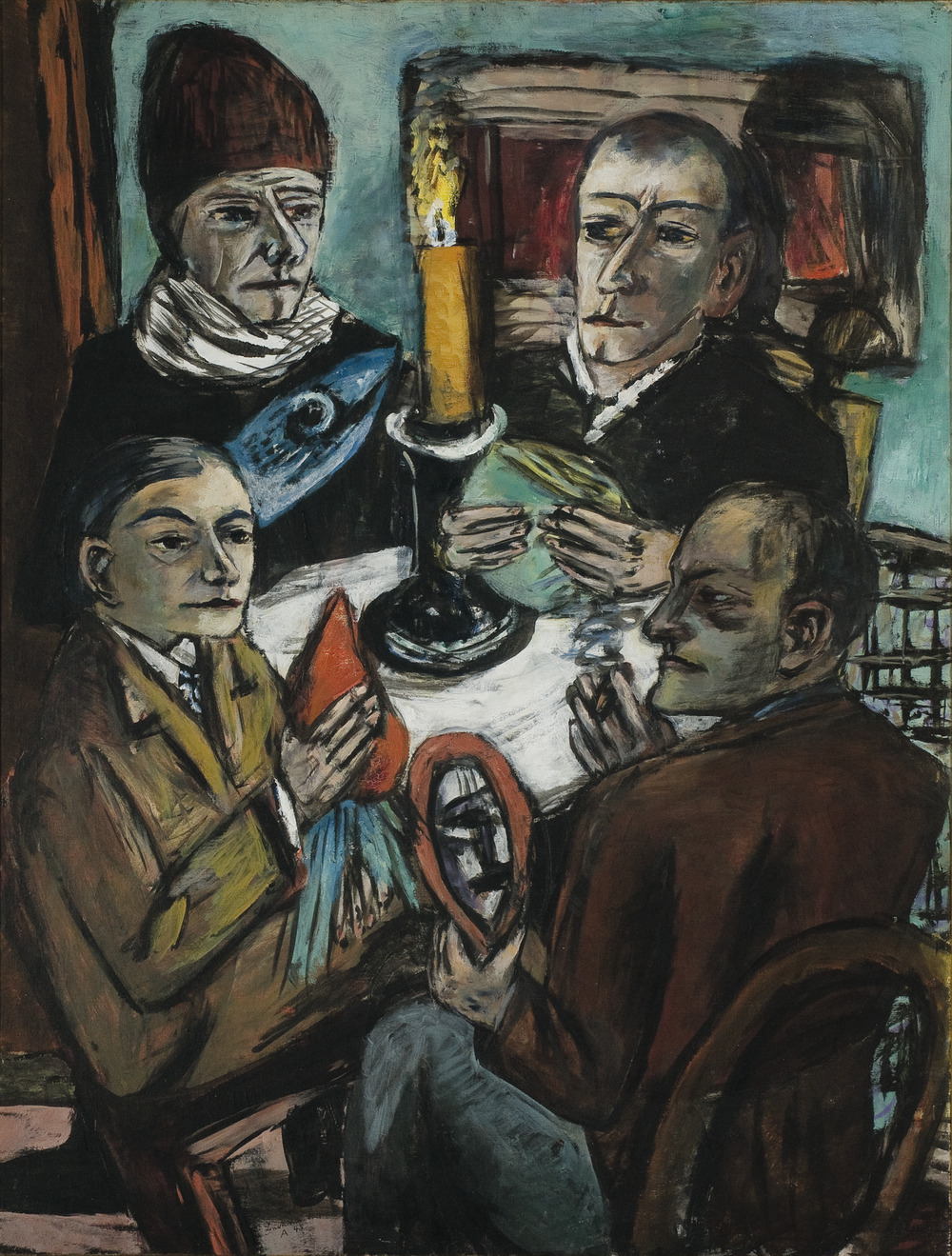

Max Beckmann, Les Artistes mit Gemüse (Artists with Vegetable), 1943

Sabine Eckmann

William T. Kemper Director and Chief Curator, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

Between April 6, 1942, and January 17, 1943, the German artist Max Beckmann, who was living in exile in Amsterdam, conceived his multilayered and ambiguous group portrait Les artistes mit Gemüse (Artists with Vegetable).1 During that time the world political situation was in many ways reaching a climax. The Nazi regime was in the process of implementing the “final solution” to systematically eradicate the European Jewry, and Beckmann witnessed the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany. Dutch Jews were deported to Auschwitz, and Jews throughout Western Europe were forced to wear the yellow star. Concurrently Nazi Germany incurred significant losses on the eastern front. Beckmann’s depiction of four men who appear materially deprived gathered around a small white candlelit table in a constricted interior—as if joined in conspiracy—captures this atmosphere of uncertainty, persecution, and war.

The painting is often interpreted as a paradigmatic exile artwork visualizing German artists’ and intellectuals’ resistance to the Third Reich and its derogatory cultural politics.2 It was not the image alone that advanced such a political reading but also the manner in which Beckmann constructed himself as a persecuted modernist German artist. He arrived in Amsterdam as a voluntary exile on July 19, 1937. It was a carefully chosen date: the very day Adolf Hitler gave his programmatic speech about German art on the occasion of the opening of the Große deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German art exhibition) at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and precisely one day after the opening of the exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art), which pilloried modernist art on a scale that was yet unknown.3 In his speech Hitler called for a cleansing war against modern art, denouncing it as degenerate based on its distorting depiction of the visible world, the elitism implicit in its alleged inaccessibility, its internationalism, and its Jewish and Bolshevik creators and distributors.

Despite Beckmann’s fate as one of most prominent persecuted German artists (twenty-one of his artworks were included in Entartete Kunst, and more than six hundred of his paintings were confiscated from German public collections between 1933 and 1937), his notion of the artist’s involvement in the political sphere was highly ambiguous, and not only during his exile from 1937 to 1947. Beckmann’s writings on art and politics situated the artist as belonging to an elitist and spiritual world autonomous from politics. For example, in his 1927 essay “The Artist in the State,” he defined the artist as a shaper of transcendent ideas in order to carry on the project of humanity.4 In a similar vein, in his 1938 speech “On My Painting,”5 delivered at the opening of the Exhibition of 20th-Century German Art at London’s New Burlington Galleries (initially envisioned to protest the exhibition Entartete Kunst),6 Beckmann reinforced a separation between the spiritual and political realms, embedding the artist firmly in the former. “Painting is a very difficult thing. It absorbs the whole man, body and soul—thus I have passed blindly many things that belong to real and political life.”7

However, Beckmann’s diaries from his Amsterdam exile give a different impression; in them all aspects of his life interpenetrate. His philosophical musings appear tied to the political situation, and considerations of his status as an exile are interspersed with reports about his daily life, his health, and his career. Seamlessly interwoven are observations regarding the transportation of Dutch Jews to concentration camps, his continuing success on the German art market (effected by the modernist art dealer Karl Buchholz, who was also under orders to confiscate modern art for the Third Reich), Beckmann’s creativity in exile, and reflections on his identity. These writings articulate his strong, almost fatalistic feelings about his homelessness, both on a metaphysical level and on one grounded in the realities of his uprooted life.

The interpenetration of intellectual concerns, actual exile experience, and political realities evident in Beckmann’s diaries parallels the aesthetic strategy he employed in Les artistes mit Gemüse. The title itself conveys a sense of irony or even cynicism about the status of the modern artist during the Third Reich. This is accomplished by its combination of French and German, indexical of Beckmann’s status as exile and of the loss of a mother tongue. While the French artistes emphasizes the superiority of the creative individual, the elitist or even transcendent role of the artist, the German Gemüse (vegetable) faces the facts of artistic life in wartime Amsterdam.

The painting depicts four cultural figures in exile: the abstract and constructivist painter Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (1899–1962) in the lower left corner; the figurative painter Otto Herbert Fiedler (1891–1962) above; to his right the philosopher Wolfgang Frommel (1902–1986); and at the bottom right Beckmann himself. Each exile holds an object, only one of which clearly resembles a vegetable: the carrot or turnip held by Vordemberge-Gildewart. Fiedler’s object is a fish; Frommel’s resembles a loaf of bread, a booklet, or possibly a cabbage but is ultimately unidentifiable; and Beckmann holds a mirror in his left hand. These objects take on the character of attributes, for which various readings exist. Vordemberge-Gildewart’s carrot or turnip has been read as a symbol of money as well as of wartime deprivation. The fish in Fiedler’s hand might stand for fertility, be a sign of recognition among believers, or represent food for sacred meals.8 The mirror in Beckmann’s left hand reflects a strongly lit and somewhat distorted clown face. In comparison to his actual profile, which is the only dark face in the image, this heightening encourages interpretations that distinguish the artist as an outsider and isolated individual. The double self-portrait also invites readings that center on Beckmann’s identity negotiated by and through the other men, whose faces are, in contrast to Beckmann’s, partially lit by the candle, suggesting a spiritual mood and linking the three exiles.

But how do these artists relate to Beckmann, and what do they have in common with him? What are their positions toward the Third Reich, politics, and their situation as exiles? Beckmann was fifty-eight years old when he executed Les artistes mit Gemüse. The other men pictured were much younger, but all four were isolated from both the Dutch art world and the German exile community, and none was active in antifascist resistance. These shared factors suggest an emphasis on the conditions of exile rather than a focus on the spiritual world.

Vordemberge-Gildewart had moved in 1938 to Amsterdam, where he worked in advertising. Prior to his exile, which was necessitated by his wife being Jewish, he had lived in Hannover, Berlin, and Switzerland. He was a member of de Stijl in 1925 and of the group Abstraction-Création in 1931, and between 1940 and 1944, together with a group called Underground, he produced illegal publications on Hans Arp and Wassily Kandinsky. Today he is considered a main representative of abstract and constructivist art. Although Vordemberge-Gildewart’s aesthetic program was opposed to that of Beckmann, who was skeptical about pure abstract art,9 he, like Beckmann, kept aloof from politics and was concerned mainly with defending his aesthetic position. In contrast, the Berlin painter Fiedler, who had lived in Paris in the 1920s and was a friend of George Grosz, executed realistic portraits. By choosing to represent these painters in a group portrait, Beckmann illuminated two modes of painting decisively different from his own concerns with creating a transcendental world. His reference to both abstract art and realistic painting can thus be understood as a means of emphasizing his outsider status and his belief in an individualistic artistic practice positioned in between abstraction and figuration.

The German philosopher Wolfgang Frommel had more in common with Beckmann.10 Between 1933 and 1935 Frommel headed a radio program in Nazi Germany called “Vom Schicksal des deutschen Geistes” (On the fate of the German spirit). A follower of the German poet Stefan George who embraced art for art’s sake, Frommel was politically conservative and attempted, while subtly criticizing the totalitarian demands of the National Socialist regime, to nevertheless promote Germans as world leaders. Frommel, whose radio program included Jewish authors, took a stance in between acquiescence and resistance. His 1932 programmatic publication The Third Humanism exposes a utopian-reactionary notion of the world. Devoid of anti-Semitism, it assumes an elitist intellectual position. Like Beckmann, Frommel privileged spiritual values, which he attempted to set against the visible world of National Socialism. Yet he also shared beliefs with the Nazis: he defended nationalism and Nazi ideals of the simple life; he mythologized the state and history in irrational ways; and he resisted progressiveness and modernity. In the summer of 1935 he was denounced, and in 1937 he left Germany for Amsterdam, where he worked for publishers and also sheltered Jews. He is undoubtedly the most important exile depicted in this painting, a point emphasized by the golden frame surrounding his head. With Frommel’s portrait Beckmann references both political positions and spiritual life; he shared with the philosopher a passion for the classical intellectual world as well as contempt for racial persecution.

The painting’s unnatural color, simple shapes, rough brushwork, and distorted perspective distinguish Les artistes mit Gemüse as clearly indebted to a modernist idiom. Yet typologically Beckmann also drew on traditions of seventeenth-century northern European group portraiture (as exemplified by Peter Paul Rubens’s Self-Portrait in a Circle of Friends from Mantua [1602–4]), thus taking up a convention specific to his place of exile. This historicist reference can be seen as an attempt to assimilate with northern culture, although not with contemporary art as it was then practiced in the Netherlands. Seventeenth-century northern art had been held in high esteem by German collectors and museums since the founding of the German Reich in 1871. Dutch and Flemish art of the seventeenth century as well as Italian Renaissance art were seen as symbols of power and intellectualism, an appreciation that continued well into the Third Reich, as Hitler’s selections for his envisioned Linz Museum demonstrate. Beckmann was certainly aware of this. Although he never would have intended any association between his group portrait and the aesthetic preferences of the Nazis, Hitler’s all-encompassing politicization of art, used to legitimize National Socialist ideology, makes possible such parallels. However, seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish group portraiture not only was highly valued by the Nazis and significant to Beckmann’s place of exile, but also encompassed metaphysical notions such as immaterial presence and spiritual content that were at the very center of his intellectual interests.

In accordance with Beckmann’s conception of modernism as an independent venture, Les artistes mit Gemüse is not informed by any actual event that might have brought these four men together. Instead Beckmann constructed a discourse that ambiguously alternates between creating a fictitious narrative and representing individual German exiles. All four are known to have lived as exiles in the Netherlands, where they shared a common fate, and their sitting together around a table suggests a probable situation. Moreover, the red background behind Frommel’s head implicates the theater of war penetrating into the small interior, emphasizing their collective experience. Other elements of the composition underscore their individuality. The figure of Beckmann, for example, avoids any visible interaction with the others that would suggest a narrative line. In addition, the white tablecloth, the large candle in its center, and the attributive character of the objects that the exiles hold in their hands establish a religious or at least pseudo-religious context, elevating the meeting into a transcendental realm in which Frommel again takes center stage, as he seems to be dressed as a priest. Beckmann’s dual demands on narrative and representation, group and individual, collectivism and individualism, illuminate both his perception of the unavoidable penetration of political realities into the aesthetic realm and his desire for a utopian practice of modernism in which art, detached from politics, “is the mirror of God embodied by man.”11

Originally published in French as “Quatre hommes autour d’une table,” in Beckmann: Centre Pompidou, ed. Didier Ottinger (Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2002), 274–78.

- 1 Beckmann worked on the painting on April 6, 1942; August 12, 1942; October 9, 1942; October 23, 1942; January 1, 1943; and January 17, 1943. See Erhard Göpel, ed., Max Beckmann: Tagebücher, 1940–1950 (Munich: Piper, 1984), 44, 50, 52, 53, 58.

- 2 See, for example, Carla Schulz-Hoffmann and Judith C. Weiss, eds., Max Beckmann Retrospective (St. Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum; Munich: Prestel, 1984), 286; Charles W. Haxthausen, “Max Beckmann: Les Artistes mit Gemüse,” in A Gallery of Modern Art at Washington University in St. Louis, by Joseph D. Ketner et al. (St. Louis: Washington University Gallery of Art, 1994), 102; and George Speer, “Max Beckmann: Les Artistes mit Gemüse,” in H. W. Janson and the Legacy of Modern Art at Washington University, by Sabine Eckmann (St. Louis: Washington University Gallery of Art; New York: Salander O’Reilly Galleries, 2002), 56.

- 3 See Stephanie Barron, ed., Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-garde in Nazi Germany (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: Abrams, 1991); and Klaus-Peter Schuster, ed., Nationalsozialismus und “Entartete Kunst”: Die Kunststadt Műnchen 1937 (Munich: Prestel, 1987).

- 4 Max Beckmann, “The Artist in the State” (1927), reprinted in Max Beckmann: Self-Portrait in Words; Collected Writings and Statements, 1903– 1950, ed. Barbara Copeland Buenger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 287–90.

- 5 Max Beckmann, “On My Painting” (1938), reprinted ibid., 298–307.

- 6 See Cordula Frowein, “Ausstellungsaktivitäten der Exilkünstler,” in Kunst im Exil in Großbritannien, 1933–1945 (Berlin: Fröhlich & Kaufmann, 1986), 35–38; Stephan Lackner and Helene Adkins, “Exhibition of 20th Century German Art, London 1938,” in Stationen der Moderne (Berlin: Berlinische Galerie, 1989), 314–37; and Keith Holz, Modern German Art for Thirties Paris, Prague, and London: Resistance and Acquiescence in a Democratic Public Sphere (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2004).

- 7 Beckmann, “On My Painting,” 302.

- 8 See Barbara Buenger, “Antifascism or Autonomous Art: Max Beckmann in Paris, Amsterdam, and the United States,” in Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, ed. Stephanie Barron and Sabine Eckmann (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: Abrams, 1997), 61–62.

- 9 For example, in his 1938 speech, Beckmann said, “I hardly need abstract things, for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can make it real only by means of painting.” Beckmann, “On My Painting,” 302–3.

- 10 For more on Frommel, see Michael Philipp, “Vom Schicksal des deutschen Geistes’: Wolfgang Frommels oppositionelle Rundfunkarbeit in den Jahren 1933–1935,” Castrum Peregrini 209, no. 19 (1993): 124–40.

- 11 Beckmann, “Artist in the State,” 288.