Anyone who knows even the smallest thing about Anselm Kiefer will have gathered that his ambitions are not ordinary. An old-school history painter, didactic and inescapably moral, he works on a grand scale in lead, sand, gold leaf, copper wire, broken ceramics, straw, wood and even diamonds, his ideas informed by, among many other subjects, the Holocaust, Egyptian mythology, the architecture of Albert Speer, German Romanticism and the poems of Paul Celan. He is the kind of artist whose physical presence – in his black T-shirts and rimless spectacles, he puts one in mind just lately of an executive from Apple – always comes as a surprise. How, you wonder, can a man who deals with so much weighty stuff have such regular-looking shoulders, such ordinary biceps? And why is he smiling? Doesn’t the darkness ever threaten to engulf him? Doesn’t his project – now more than 40 years old – sometimes pinch at his sanity?

Yet only with the help of a blindfold would you be able to wander the Royal Academy’s stupendous retrospective of his work and leave feeling anything less than drunk with amazement. However much you know about Kiefer, it’s impossible to be prepared for this show: for its scale, its pleasures, its provocations and – this must be said – its bafflements. This is a total experience. The work first speaks to the eyes, which instinctively scour every last corner of every painting, every sculpture. Then it calls to the heart, pulling from you all sorts of things Kiefer certainly didn’t intend (in my case: modern-day Syria; the 80s nuclear TV drama Threads; John Wyndham’s novel The Day of the Triffids). Last of all, it engages the head, as you attempt to unravel his complex, multilayered narratives. It’s certainly useful to know your history before you enter these spaces – and if you’re fluent in the language of Richard Wagner and Caspar David Friedrich, so much the better. But it isn’t necessary. In any case, mystification is half the point. No artist puts this much effort into the construction of their work without wanting their audience to linger over it, to try and fathom it out.

Kiefer was born in the Black Forest in 1945, a kind of year zero in terms of German history. And it’s this – the attempt to wipe out collective memory after the war – that has long been his creative wellspring (at school his teachers hardly mentioned the Third Reich). Taught by Joseph Beuys, the artist who helped Kiefer’s generation to reclaim much of the historical and mythological imagery rendered so toxic by the Nazis, his early work depicts himself, dressed in his father’s army uniform, taking the Nazi salute outside the Colosseum in Rome and elsewhere. The Royal Academy show, which works chronologically, begins with this zesty, youthful reappropriation. I was queasily hypnotised by the watercolour Ice and Blood (1971), in which an expanse of snow is scarred with pools of crimson and, far worse, a tiny, naive figure in a military overcoat, its right arm ominously raised. Before you get there, though, the Royal Academy reveals its breathtaking commitment to Kiefer with a little reappropriation of its own. The garish shop at the top of the gallery’s stairs has disappeared. In its stead is Language of the Birds (2013), a monumental sculpture comprising a pile of charred-looking books with a huge set of wings attached. Do these belong to a German eagle? Naturally, that’s what comes to mind. But I kept thinking, too, of the phoenix, a creature that speaks to Anselm’s preoccupation with myth, rebirth and the cycles of time every bit as loudly as the Reichsadler.

The phoenix rises from the ashes, and this, after all, is a show that is covered in clinker. Ash Flower (1983-97), made of oil, acrylic, paint, clay, earth, ash and – a recurring symbol in Kiefer’s work – a dried sunflower, is a seven metre-wide depiction of a ruin, the ruthless lines of a grand public building emerging through its murky surface like the prow of a ship through fog. Sulamith (1983), inspired by a Paul Celan poem, Death Fugue, which was written in a concentration camp (“your ashen hair Shulamite”), is a gloomy crypt rendered in oil, acrylic, woodcut, emulsion and straw, at one end of which a fire endlessly flickers. Untitled (2006-08) consists of a triptych of huge vitrines in which there resides a wintry graveyard of brambles, dead roses, more ash, and toppling concrete houses. Gradually, the work starts to talk to the future as well as the past. In the Royal Academy’s octagonal gallery is a new piece, Ages of the World (2014): a pile of abandoned canvases and rubble bedecked with an unhappy coronet of yet more dead sunflowers. It has a dystopian, post-apocalyptic feel: no culture, no hope.

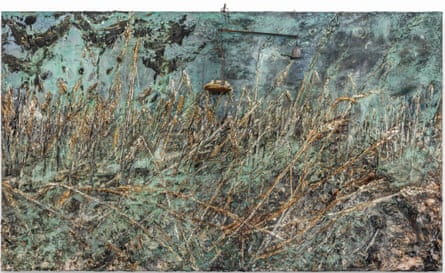

All this is pitch-dark. But there is radiance elsewhere – and colour too. For Ingeborg Bachmann: the Sand from the Urns (1998-2009) is a depiction of a ziggurat in a sandstorm so astonishingly dynamic you’re almost tempted to squint, the better to protect your eyes, while the satirical Operation Sea Lion (1975) has toy battleships floating in one of the zinc baths that were given to every German home by the health-obsessed Third Reich, its water a horribly chipper shade of blue. Best of all there are Kiefer’s Morgenthau paintings from 2013, named for the US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jnr – whose plan it was in 1944 to transform Germany into a pre-industrial nation as a means of limiting her ability to fight future wars – and crammed with impasto stalks of corn that sometimes blow and bend, and sometimes reach for the blazing sky. A note on the wall urges the visitor to note the crows circling above, a symbol of death and resurrection. But it isn’t these flapping shadows that keep you in the room; it’s the whispering grass, the beatific sunshine, the splashes of cornflower blue. Kiefer is that most resolute of artists. He has never turned away from the difficult and the sombre; his career is a magnificent reproach to those who think art can’t deal with the big subjects, with history, memory and genocide. In the end, though, what stays with you is the feeling – overwhelming at times – that he is always making his way carefully towards the light.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion