Just like this year’s, the heatwave in 1976 arrived as Britain seemed to be approaching an economic and political abyss. During the spring and early summer, as the sun began to hammer down and the usual rain failed to fall, and the reservoirs began to shrink, the pound was lurching downwards on the markets. For almost three years, under Tory and Labour governments, the economy had been shrivelling alarmingly. Just as since the Brexit vote, a conviction had been building like a thundercloud among financial traders and business leaders, economists and commentators, in Britain and beyond, that the country was about to slip to a lower, less elite level, and stay there. “Goodbye, Great Britain,” said a much-read editorial in the Wall Street Journal in 1975, “it was nice knowing you.”

Q&AShare your memories from the summer of 1976

Show

If you remember the British summer of 1976 we'd like to hear from you. What do you remember? How does it compare to this year?

You can share your photos and memories by filling in this encrypted form. One of our journalists may be in touch and we will consider some of your responses in our reporting. You can read terms of service here.

To some pessimists about Britain’s prospects, the drought the following summer, which brought forest fires, crop failures, hosepipe bans enforced by policemen and vigilantes, and standpipes on street corners instead of mains water, was a further sign of crisis. In 1976, with impeccable timing, the American writer Paul Theroux published The Family Arsenal, a bleakly satirical novel about terrorists on the loose in a sweaty, rundown mid-70s London, its “decay pushing towards ruin”. Some sort of apocalypse, predicted one of the characters, was “certainly coming”.

But the Labour chancellor, Denis Healey, was not one of the worriers. In the summer of 1976, after several exhausting months trying to defend his economic policies and the value of the pound, he went on holiday for most of August. He left sticky London behind and drove unhurriedly through England and Wales and up to north-west Scotland. “Not a drop of rain,” he wrote in his memoirs, “even in the Highlands.” In the hidden away lochside town of Ullapool, Healey checked into a hotel on the quayside and began to relax.

That night, he was repeatedly woken by phone calls from Whitehall. In the US currency markets, the pound was collapsing again. The hotel had only one phone, so the chancellor stood in a hallway with a coat over his pyjamas, authorising the Bank of England to spend “up to $150m” (about £750m now) to buy sterling. The intervention worked: the pound stopped falling. Healey went back to bed, and then continued with his holiday.

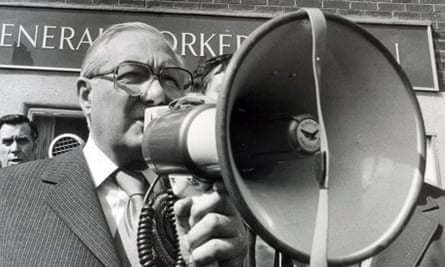

Hot weather does contradictory things to British politics. In parliament, with its stuffy rooms and sweaty dress codes, it traditionally sparks revolts, plots, panics and flashes of temper – a sense that things are coming to a head – as it has this summer. Yet away from Westminster, a heatwave can make politicians, and even more so voters, worry less than usual about the state of the nation. In an overcast country, sunshine often means contentment and escapism – and procrastination. During July and August 1976, despite the state of the economy and a widespread disillusionment with centre-left politics (which had been deepening since the late 60s), the Labour government pulled level with the Conservatives in the polls. Healey was generally seen as a tough, capable chancellor. The prime minister, Jim Callaghan, had an avuncular, calming manner that seemed appropriate to the summer lull. Voters called him Sunny Jim.

Theresa May has none of Callaghan’s sly charm. But her situation this summer is similar in some ways. As in 1976, a divided government in a weak parliamentary position, wedded to increasingly contested ideas – for Callaghan, postwar social democracy, for May, austerity and the free market – has somehow made it to the welcome shade of the recess, despite many predictions to the contrary. The main opposition party remains ominously strong, but it has an intensely divisive leader whom many voters see as odd and extremist: in this sense, Margaret Thatcher was the Jeremy Corbyn of the mid-70s.

And, just as Callaghan did, May has managed to put off the most difficult political question of her government until the autumn. In 1976, this was whether Britain could afford to continue with its postwar levels of state spending; now it is how to do Brexit. Yet during what might be a once-in-a-generation summer – as the sun keeps shining, day after day, and the parks are full of impromptu skivers, the pubs are full of workers having cheeky afternoon lagers, and even supposedly earnest protest marches feel more like carnivals – such national dilemmas can feel very distant.

In the summer of 1976, the sense of ease was not a total delusion. Twenty-eight years later, the respected New Economics Foundation created a measure for overall economic, social and environmental wellbeing, and concluded that 1976 was the best year in modern British history.

For those invested in the idea that the 70s were a nadir for Britain – pro-Thatcher historians, and hipper archivists of the punk rebellion against the mid-70s status quo – the summer of 1976 has always been an awkward piece of counter-evidence. Yet as Jon Savage pointed out in his 1991 book England’s Dreaming, still the best, most nuanced study of punk and its political and social context, the heatwave actually helped the movement. After dark, the rare warmth gave the first British punks a sense of possibility, and a freedom, as they roamed between squats and nightclubs. In a normal British summer, it would have been hard to stay out all night in punk outfits full of holes.

The summer of 2018 feels less carefree. We know more about climate change and skin cancer now. This week, forecast to be the hottest of the season, the Met Office is advising people to stay out of the sun. And the world beyond Britain feels more genuinely apocalyptic, and harder to ignore. We face Trump and a Europe increasingly controlled by far-right populists; in the summer of 1976, the continent was dominated by centrists, and the insurgent shaking up US politics was a mild, almost meek Democrat, Jimmy Carter. Even the cold war seemed to be abating, thanks to the disarmament treaties and subtle diplomacy of detente.

But we shouldn’t idealise the summer of 1976 too much. Away from its unexpected pleasures, pressures were still building in Britain. In August the guitarist Eric Clapton near the peak of his fame, used a concert in Birmingham to make a speech defending the anti-immigrant prejudices of Enoch Powell. At the end of the month, the Notting Hill carnival in London turned into a battle between the police and black youths, a prefiguring of the many riots in the decade to come.

Also in late August the heatwave finally disintegrated in a mess of thunderstorms. A soaking, grey autumn followed. The pound resumed its decline, the government’s finances deteriorated further, Whitehall panicked – or, some say, exploited the situation – and the government ended up drastically cutting its spending, and accepting a loan from the IMF. The reputations of Healey and Callaghan, their government, and postwar social democracy, never quite recovered.

Once the summer interlude of 1976 was over, Britain changed very fast – and in many ways not for the good. Perhaps that’s something for Theresa May, and the rest of us, to ponder while we enjoy the sun.